Our titular monster pal appears to be on some kind of lonely school trip to an open air museum dedicated to the weirdness of humans from “Englandland.” It’s spread out among an archipelago, which plinths displaying examples of human culture, each with a plaque recording their use or import. There are no bridges but plenty of helpfully placed trees for felling and chucking into the water to DIY your own. There are two different kinds of logs that act in different ways, and that’s it. Everything else is just island and obstacle design, introducing new delightful tricks little by little. There’s no explicit tutorial, but even without paying attention you’ll pick it up one new thing at a time until you’re surprised by how internalised it all is. Look a little closer, and it’s stunning to notice how each island is set up just so to help you figure it out. There’s a moment not long into the game where the process of following the puzzle solution you think you understand leads to something very unexpected. I won’t spoil it, because it’s a lovely moment, but the thing to know is that the rules haven’t changed in the slightest. You’ve just used them in this way for the first time. That continues throughout the game. Nothing new is introduced, exactly, it’s just that the islands are set up just so, enabling another interaction to become clear.

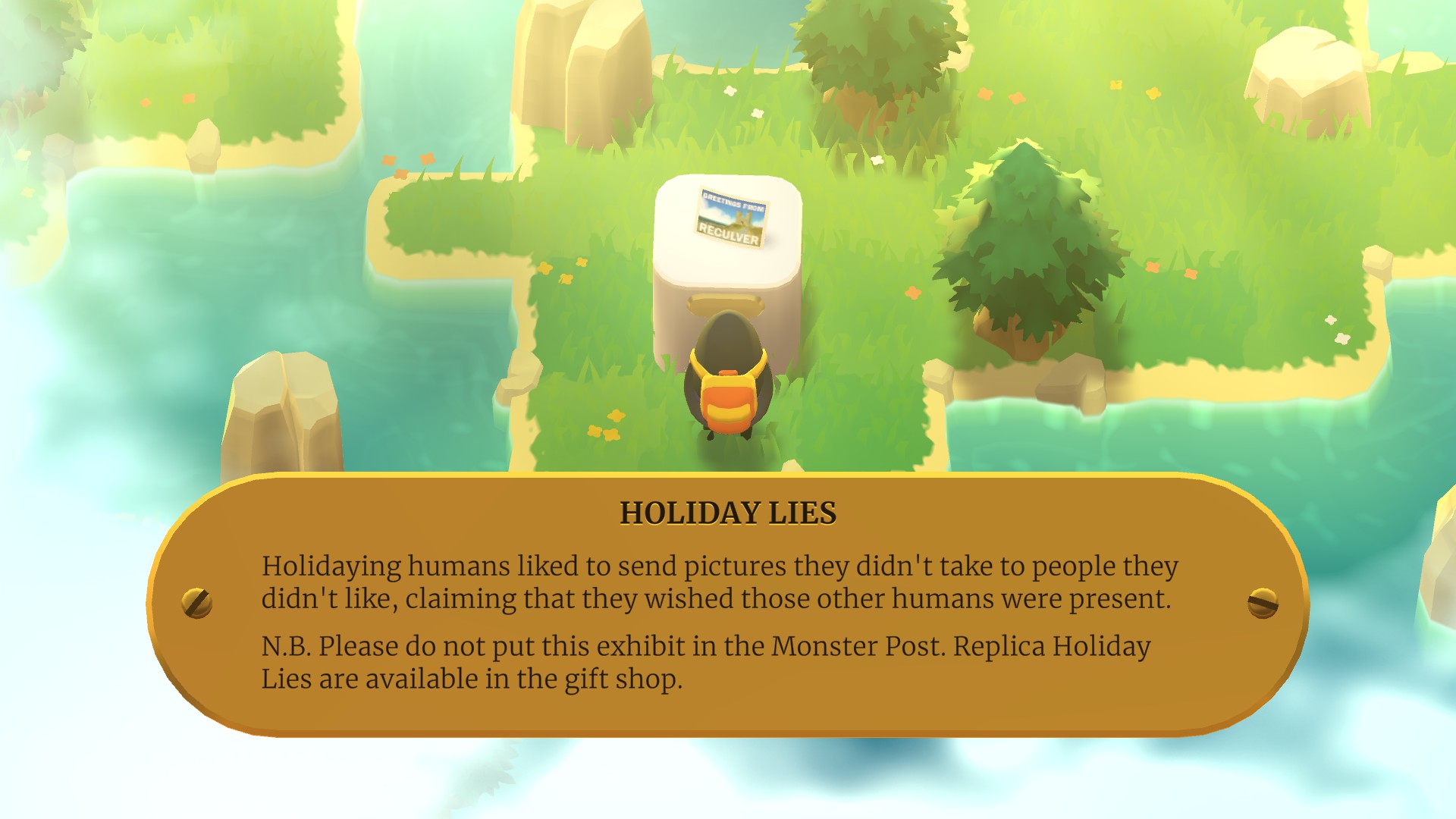

Thinking about the level of craft necessary to make this work makes my brain break a little. Not only is each individual island cleverly set up with their own puzzle or two, the world map is linked up, maze-like, allowing you to wander as you please. Get stuck? Simply meander back to another part that’s still fogged over waiting to be solved. Head towards one of the towering exhibitions, like the rollercoaster, or go hunting for particularly out of the way puzzles, up to you. There are post boxes dotted around the map to warp between, so it’s not a big deal to get around whenever you want. There’s nothing mechanical breaking up the different areas, but each has its own aesthetic biome, with, say, cherry blossoms or giant mushrooms giving the soft arborealism a new vibe. It doesn’t change too much, but that’s fine, because the whole game already has the feeling of a sunny April morning. Sometimes, you’ll find a little coffee stand just waiting to give you a break. And at any moment it’s possible to just sit on the shore, feet dangling into the waves as the camera slowly pans out to show the sun refracting on the water and the wind nudging the grass. The music is responsive, too, flourishing scales following a rolling log or a gentle cymbal crash accompanying an undone move, like the world is gently encouraging your experimentation. The chill atmosphere doesn’t stop it from being both funny and critical, however. The snippets of writing on exhibition plaques sometimes lean a little too hard into twee Britishisms for my taste, but they usually land, simultaneously poking fun at the difficulty of interpreting archaeological finds, pointing out the imperialist endeavours of the modern museum industry, and building its own strange world of backpacked faceless monster kids. One describes a postcard as an example of “holiday lies”, where humans would “send pictures they didn’t take to people they didn’t like, claiming that they wished those other humans were present.” Replica holiday lies are available to buy in the gift shop.

Monster kid themselves, by the way, is very cute. Spend too long idling and they might wave, or else put their hands on their hips in a clear “hmm” motion right as you’re sitting with your own face screwed up and hand on your chin in similar consideration. Close and reopen the game and the menu screen will show them napping on the grass right where you left them. Jealousy inducing. It’s all these touches that form an important secondary effect next to teaching the player how to play so effectively. Getting stuck and backtracking to a different area, or even just sitting staring at one spot, is so much less frustrating than it easily could be. At times when I thought it’d be best to get up and make some tea or something to get some space from a puzzle, I usually found myself just heading down a new branch and getting straight back into the swing of solving things again.

It helps, too, that A Monster’s Expedition has no interest whatsoever in being frustrating in the first place. You can always reset an island without messing up anything else you’ve done elsewhere, crucial for the ability to wander off somewhere else if you want to. There’s no meter counting how many moves it took or how many resets you did on any given puzzle. And there’s always the choice to go back one step, judgement free (though this one is kind of crucial given how easy it is to accidentally knock a tree down the wrong way). Basically, there’s nothing in the way of making me feel like I’ve become awfully clever at it all. As much as I can appreciate and credit its beautiful design and atmosphere for that, when I suddenly get the solution to a particular island, I get the mental round of applause all to myself, made all the sweeter by previously thinking this genre was impossible for my brain. Disclosure: Former RPS staffer Pip Warr was a writer on A Monster’s Expedition.