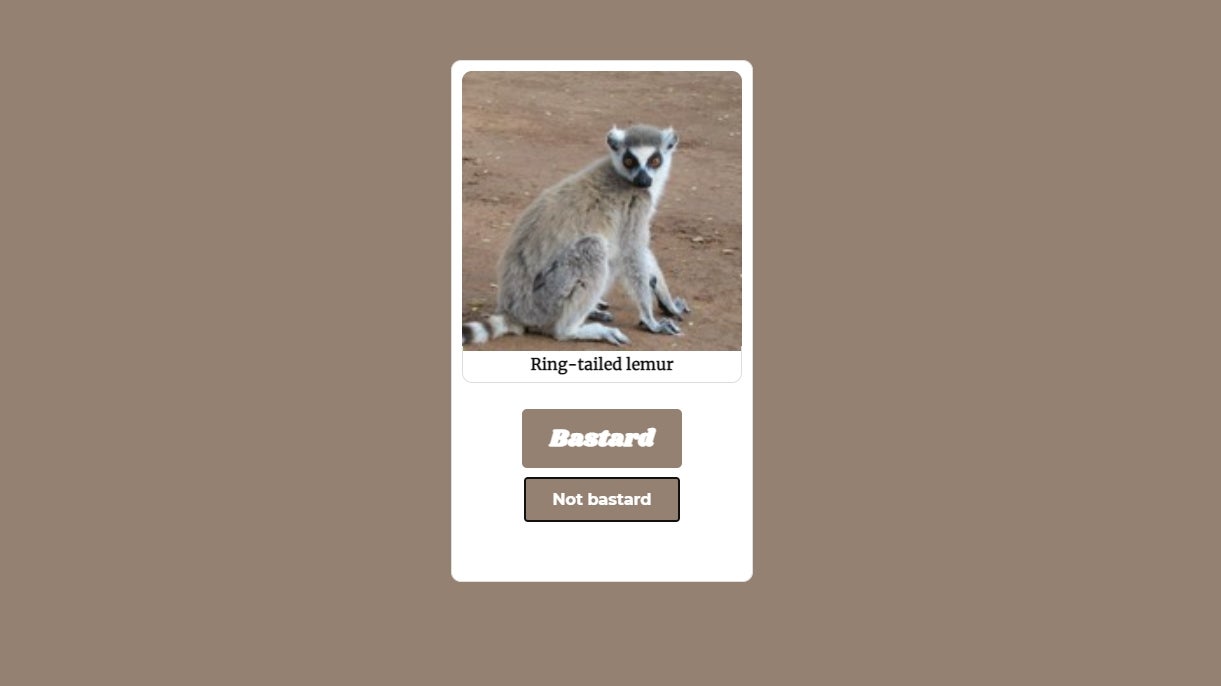

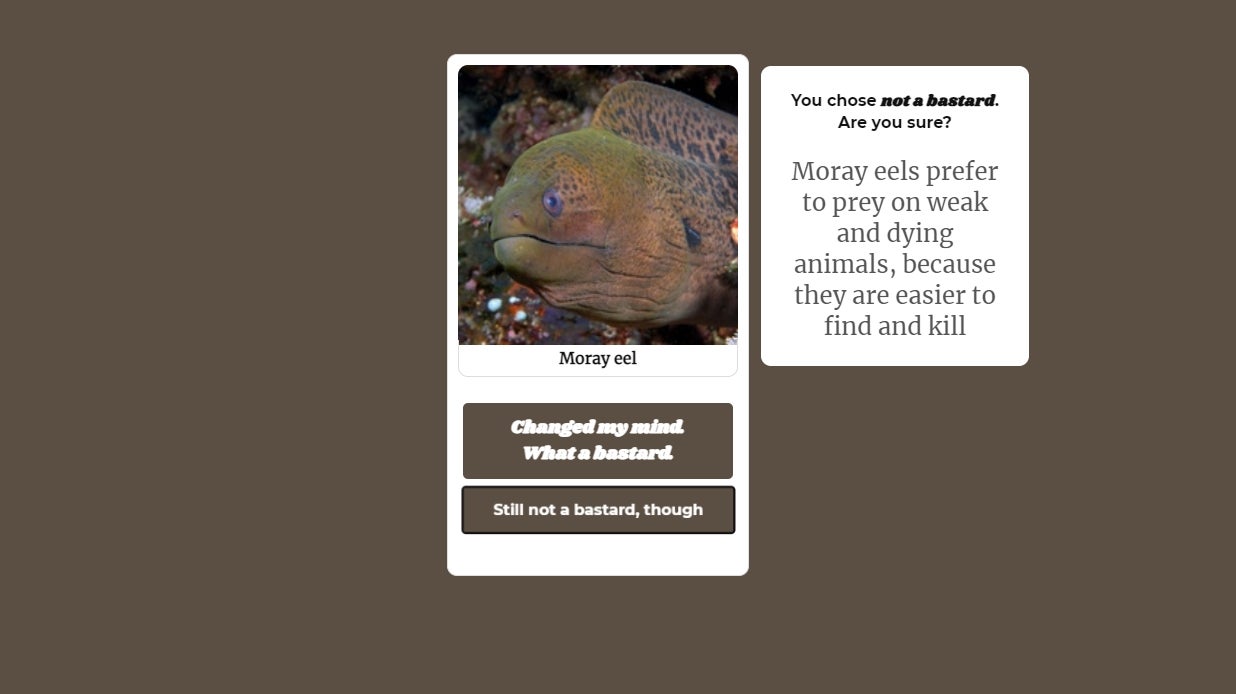

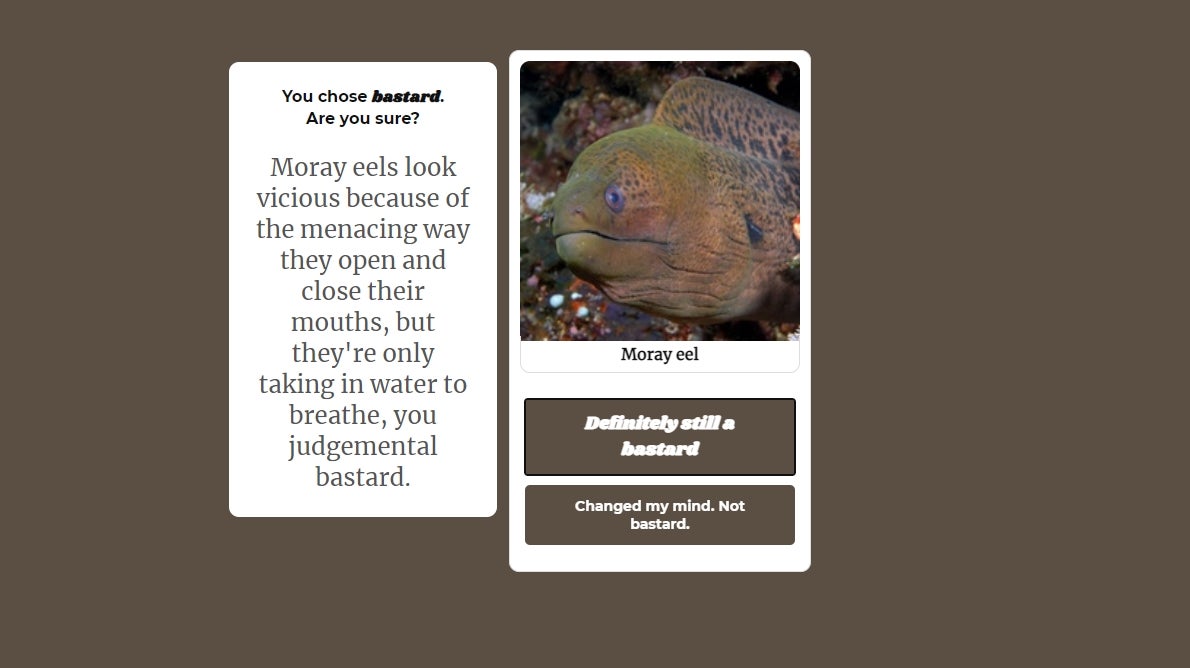

The job, by the way, was working in the education department for a zoo: we went on school visits where we showed off various small animals, and the hissing cockroaches were my “team”. I named them all after artifacts in the Dwarf Fortress I was playing at the time, and so my star performer was a lass called Chillberry, the Price Of Times. Anyway: the reason I’ve been reminded of all of this, is a splendid, simple browser game Alice0 pointed out to me, called Animal Bastards. It’s extremely funny, but it also makes an elegant point about the way we form our opinions on beasts, and I’ve been thinking about it all week. Go and play Animal Bastards, first. It’s dead simple, it’ll barely take you three minutes, and there’s no way you won’t laugh while doing it. Honestly, it’ll take you less time to play than it’ll take for me to explain it. But for the click-averse, here’s the precis: it is a game where you are shown pictures of animals, and you must judge whether they are bastards or not. Once you’ve made your call, the game will present you with a fact about the animal, after which you can either confirm or reverse your original decision. That’s it. The humour here shouldn’t take a lot of explaining. After deliberating for a good twenty seconds over a Tree Kangaroo, I actually made myself laugh with the speed at which my cursor shot towards the word “bastard”, when presented with a photograph of an ostrich thereafter. Another time, I chuckled at my resolute insistence that an eagle was “still definitely a bastard”, despite the game’s heartfelt attempt to convince me otherwise. And that’s the clever thing behind the joke in Animal Bastards. It is, very gently, prompting you to laugh at yourself for making any sort of moral judgement about an animal. It underlines this point by having a compelling case to use against you, no matter which option you initially choose in each animal’s case. Take Sleepy Lizards, for instance. Accuse them of bastardry, and you’ll be reminded that “Sleepy lizards pair for life. If one is killed on the road, the other will stay with the body, nudging it gently to try and revive it”. If you then flip-flop, and go for “not a bastard,” it will be revealed that “male sleepy lizards use their jaws to grab females by the head when mating, leaving them with visible wounds.” Now you’re the bastard. You bastard. In both instances, you’ve been potentially swayed by the highlighting of behaviour that coincides with the moral values of your own culture. In essence, you’ve been asked to decide to what extent a species’ instinctive behaviour resembles your personal ideal of human conduct. Which is a very silly way to think about an animal really, isn’t it? It made me think about the kids and the cockroaches. Because they, too, illustrated just how much our opinions on animals are imprinted on us by our parents, our teachers, and the books we read. All this has a real effect, too. Giant Pandas happen to have a tangential resemblance to baby humans. Ergo, they are “goodie” animals: they’re heroes in cartoons, they’re all over kids’ stuff, and because of all the conservation money scared up by this love-bombing, they’re doing just fine now. Toads of all kinds, by contrast, are on the list of “baddie” animals, and so a lot of people grow up either finding them vile, or just not giving a shit about them at all. The knock-on effect? Amphibians of all kinds are terrifyingly endangered, and efforts to protect them are grimly underfunded. There’s a wider point to touch on here, too. While a lot of us recognise that it’s silly to call any animals “bad”, we’re happy to go full “humans are the virus”, and make weirdly absolutist moral judgements about our own species. Just because chimps and walruses aren’t burning fossil fuels, we ascribe a weird sort of sainthood to them, and castigate ourselves for being an “evil” species. Now, I’m not saying for a moment that this makes human environmental destruction fine. Quite the opposite. My point is that we can take responsibility for what we’ve done, and act on that, while still accepting that we are still animals, who only ended up in this situation because of the lottery of natural selection. There’s no dichotomy between “humans” and “nature”, is what I’m saying. Polar bears might well be grieving over pictures of us looking forlorn on tiny icebergs, had they ended up developing global environmental dominance as an evolutionary survival strategy, instead of us. Toads might be failing to deal with the fungal plagues killing us off. And we’d be just as dependent on the bears or the toads to clean up their fucking act, as they currently are on us. It wouldn’t make ‘em bastards, though; just animals, same as we are. Animal Bastards is not half as po-faced as I am about all this. And it is, of course, perfectly valid just to play it and call an animal a bastard, because it has what you consider to be the face of an inveterate bellend. The game is, at the end of the day, a fun joke. But like all the best fun jokes, it pulls some interesting brainstrings.