Enter Black Mesa, a fan-made remake of the original Half-Life, inside Half-Life 2’s Source engine. Over 8 years since we first reviewed its earliest release, the project is now complete. It is a triumph on many levels, and in terms of scale and polish, the most impressive fan game ever made. But it remains, underneath, Half-Life - with all that that entails. If you’ve never played Half-Life before, both it and Black Mesa cast you as Gordon Freeman, a 27-year-old scientist arriving for work at an underground research facility. You’re there to conduct an experiment, which goes wrong in typical B-movie style: portals open, alien monsters are unleashed, and the facility descends into chaos. You must fight your way back to the surface, contending with aliens and military clean-up crews, both of which are equally determined to kill you and every other scientist in the facility.

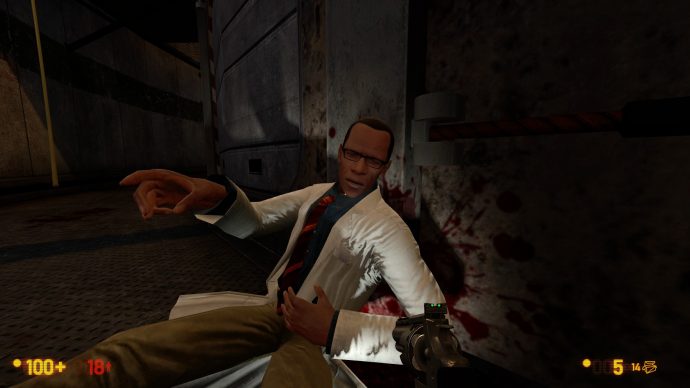

To be clear: Half-Life might have aged, but it is still a good game. Its environment design is still evocative despite its visual shortcomings, its shotgun is still fabulous at right-click-exploding enemies in satisfying showers of alien body parts, and its storytelling methods are still the template for the twenty-two years of first-person shooters that followed it. As you weave through Black Mesa’s warehouses, railways and sewage systems, fighting ninjas and flipping switches, it will become clear that the world of game design has moved on, but that Half-Life’s relatively simple horror tale holds up far better than most of its peers. Black Mesa follows the beats of the original game exactly, through each of its now-famous moments. The opening tram ride is extended and refreshed with larger, fancier scenery. The slow walk through the Black Mesa laboratory has the same sights and jokes, but with the newly-added presence of Eli Vance. The resonance cascade, which is what unleashes the mardy aliens from Xen, is enlivened by actual physics interactions, and many more particle and lighting effects than the original Half-Life could manage. Beyond that, there are the same scripted sequences, the same relentless commitment to the first-person camera, and the same eventual trip to Xen itself at the end.

Each of these elements once made Half-Life phenomenal, but in every case, part of the initial thrill has been dulled by time. I’d never seen anything like that opening tram ride in 1998, or the slow moments of pre-disaster exploration that follow. “Scripted sequences”, in which scientists would animate and talk and meet their grisly demise as you came upon them, were a revelation that made Half-Life’s world more alive than any first-person shooter’s before it. We don’t call these moments “scripted sequences” anymore though, because they’re so commonplace they don’t need a name. It’s bizarre to remember that “things happen” was once a back-of-the-box feature. Black Mesa’s meticulous recreation does not return any of these moments to their former glory, because to do so would be impossible. You can’t see something for the first time twice. As a result, moments like the tram ride now feel overly long, even dull, as they lock you in a small box to deliver exposition and worldbuilding I’d expect a modern game to parcel out more elegantly. What Black Mesa offers instead is a visual refresh that successfully drags 1998’s finest level design to a visual standard mostly set in stone around 2010, using a 2004 engine. It does so with grace and flair. Often, visual remasters do a terrible disservice to the original artwork of older games, jamming polygons, high-resolution textures and greebles onto every surface with little consideration for original intent. To its enormous credit, Black Mesa doesn’t do that: the spirit of each location is maintained, whether the early labs, the wood-panelled offices, or the cavernous bowels of the facility. It never feels like the level designers are using the increased fidelity available simply because they can.

The familiarity of it all offers some advantages, too. If, like me, you’ve played the original game multiple times, you might find you remember each twist and turn over the course of the game’s first 3-5 hours. There are some changes - a brief section where you set zombies on fire with flares, before finding the crowbar, for example - but otherwise it’s moment-by-moment unchanged from the original game. I sped through the game’s first eight chapters, blasting apart houndeyes, vortigaunts and military grunts while barely pausing to think. It falls apart only when something breaks this flow state. There are jumping challenges that are no more fun now than they were the first time around. There are moments in levels where it’s easy to lose sight of where you’re meant to be going, or to find the exit from a combat arena. These problems would be solved in a truly modern game via player testing and layout changes, or by a friendly NPC buzzing in your ear to point you in the right direction. Or even by a big quest arrow pointing to where to go. Your objectives also make progress a slog for the game’s third quarter, from the chapters ‘On A Rail’ through to ‘Lambda Core’. There are memorable moments within, including the enormous Garg, and being thrown in a trash compactor by enemy soldiers, but the rest feels repetitive. But then, did fighting the Alien Grunts and military ninjas ever feel good? In retrospect, Half-Life represents a sort of mid-point between different eras of action game design. The first-person shooters that came before it were defined by Doom and Quake: running and gunning in relatively static worlds, divided by locked doors, with enemies who wanted nothing but to fill you with bullets. The games that came after, and which are made today, share more in common with Half-Life 2, with set-piece design structured around giving players a new toy for the duration of a single level. For example, Half-Life 2’s Ravenholm, which gives you sawblades with which to slice zombies in half, after which you never see another sawblade for the rest of the game.

Black Mesa sits in the middle between those two poles. There is more to its world than just enemies who want to kill you, but you’ll still be running and gunning for most of your time. You’re never looking for a blue keycard to open a blue door, but neither are you being offered novel toys, and problems specifically designed to be solved by them. You’ll instead spend a lot of time heading down one corridor to restore power, then backtracking and heading down a second corridor to restore the auxiliary toxic sludge pipe, so you can eventually press a big button marked “progress”. When you are given something new to play with, such as the hornet hand, snarks, or crossbow, there’s an initial thrill. Even after two decades, the weapons feel weird and exciting, and the new animations for the hornet hand are particularly delightful. Such a broad arsenal of weapons is unusual these days, and I found real pleasure - relief, even - in always having a dozen death-dealing options in my pocket, rather than being limited. And yet, they’re also of limited use in most situations. I defaulted to the Magnum and the shotgun again and again, and even when a weapon was powerful, such as the gluon gun, I often avoided using it because it didn’t feel powerful. The gluon gun is an extremely loud and deadly hose with a substantial charge-up time, but it only causes small red splotches to appear on enemies to signify they’re being hurt - and then they simply burst. The contrast to all the game’s careful historical reenactment is Xen, the infamous muck-coloured alien homeworld which forms Half-Life’s last act. I feel like I’ve committed numerous acts of sacrilege so far by criticising other aspects of the original Half-Life, so let’s round it out by saying: Xen was never as bad as people say. Sure, it writ large the garbage jumping puzzles from the game’s earlier sections, and took place across several, small, disc-shaped turd islands, but it was still a welcome change of pace. I liked the little light bulbs which recoiled when you came near, the ecosystem of new flora and fauna, and the Gonarch’s thundering testicle.

Black Mesa retains those three things, but changes nearly everything else - and almost entirely for the better. Xen is Black Mesa’s level designers unleashed, revelling in the freedom to create something of their own. The brown islands are gone, and in their place is lush, colourful terrain. There are several gorgeous vistas to gawp at, and even distinct-feeling biomes, from alien jungles, to encroaching human outposts, to the Gonarch’s network of caves. It still feels Xen-like, and in keeping with the game’s overall style, but it’s Xen as it might have been made today. Even the jump puzzles are no longer awful - the awkward and tricky leaps between islands have been replaced with more simple traversal using a long-distance jump move. It’s properly fun. Yet it’s not perfect, either. One of the original complaints about Xen was how divorced it felt from the rest of the game. The new Xen doesn’t have that problem - but then, I never thought that was a problem to begin with. Remember what I said before, about how Half-Life chapters often boil down to trudging back and forth to power machinery and unlock progress in a central hub? Hey-hey! That’s what Xen is about too, now, with Half-Life 2’s power cables making an appearance as you use them to wire up alien crystals to provide electricity to doors, or find ways to explode other crystals in order to flood chambers and swim up towards new corridors. After following this routine for so many hours, it feels like a slog to do it all again in Xen. The Gonarch, meanwhile, is still more memorable for her visual design - she’s a big bollock, ain’t she - than for the actual fight. That fight takes place over multiple stages, including several segments where you’re being chased, during which the Gonarch is seemingly invulnerable to damage. It’s not any more fun for being longer. There’s still not enough visible feedback when shooting at her, either. It left me wondering whether I was missing something, and feeling as if I was making no progress until, eventually, she burst.

Finally, there’s the Nihilanth, Half-Life’s similarly infamous big baby boss. Gone is the portal-based chicanery of the original fight, replaced with a straightforward three-stage pounding. It is suitably epic, as the big baby wrenches rocks from the ground, pummels you with missiles, and even spawns trucks and jeeps to throw at you. For your part, it still boils down to blasting the big baby bullet sponge till, again, it bursts. But at least it looks good doing it. So, Half-Life, then. I used to say it was my favourite game of all time. Now, I’d say it’s a first-person shooter that is occasionally great, mostly good, and sometimes charmingly crap. Black Mesa smooths out most of the crap, and maintains the great and the good. It doesn’t modernise the antiquated design - but then, it wouldn’t be Half-Life if it did. As it is, it’s the best way to play Valve’s original design if you haven’t done so before, and it’s a brilliant way to retread those old ventilation shafts, if you have.