It begins with a couple of taster missions, a gung-ho chase across rooftops and an airport ambush in which you use an RC car strapped with explosives to stop an escaping plane. You never use the RC car again. This is a known offence for Call Of Duty games by now. Brief gizmos turn up between equally short-lived contrivances lifted from other games. Here you can mark enemies with a camera in a couple of levels, like in any modern Far Cry. You can sometimes have aimless chats with people, as if this were a Mass Effect game and not your annual simulation of US exceptionalism. These are reminders that COD (at least in its campaign mode) is still the cannibal of the games industry, picking the bones of other genres and franchises to create the ultimate action-game-by-commitee. To that chunk of the gaming audience who pop in to video games once a year for an explosive ridealong they saw advertised on the side of a bus, that’s probably fine. Likewise for those who like to slap on a Callodutes like it’s their favourite t-shirt and eat crisps all weekend on the sofa. This is the bulletpointed newsletter of an industry. Who needs to play detective in Obra Dinn when CODWAR lets you use a blacklight to find handprints in level three? Depending on how many games you play, this parade of novelties may feel like the peak of cinematic videogamesing, or it will be like slurping on a watery FPS soup sparsely garnished with diced cubes of other, better games.

The stand-out example is an extended mission where you wander around KGB headquarters as an undercover Soviet informant Hitman style, strangling comrades, hiding their bodies, and having a meeting with Gorbachev himself. The future General Secretary is a mirror image of Ronald Reagan, who appears in his own earlier cutscene to play the part of platitudinous daddy of the nation. But more on that in a moment. This gunless enemy HQ sequence is a continuation of previous infiltrating digressions of the series, and it’s as close to immersive sim as COD is likely to get, offering you multiple ways to complete your mission in plain sight. Will you poison a baddie? Frame him as a mole? Or convince a prisoner to kill him? Your avatar, head of security Belikov, has the best moments of the game, wriggling in suspense amid the paranoid colleagues of a Russian spy ring, including some familiar faces to fans. But like all the other toys, Belikov is soon discarded.

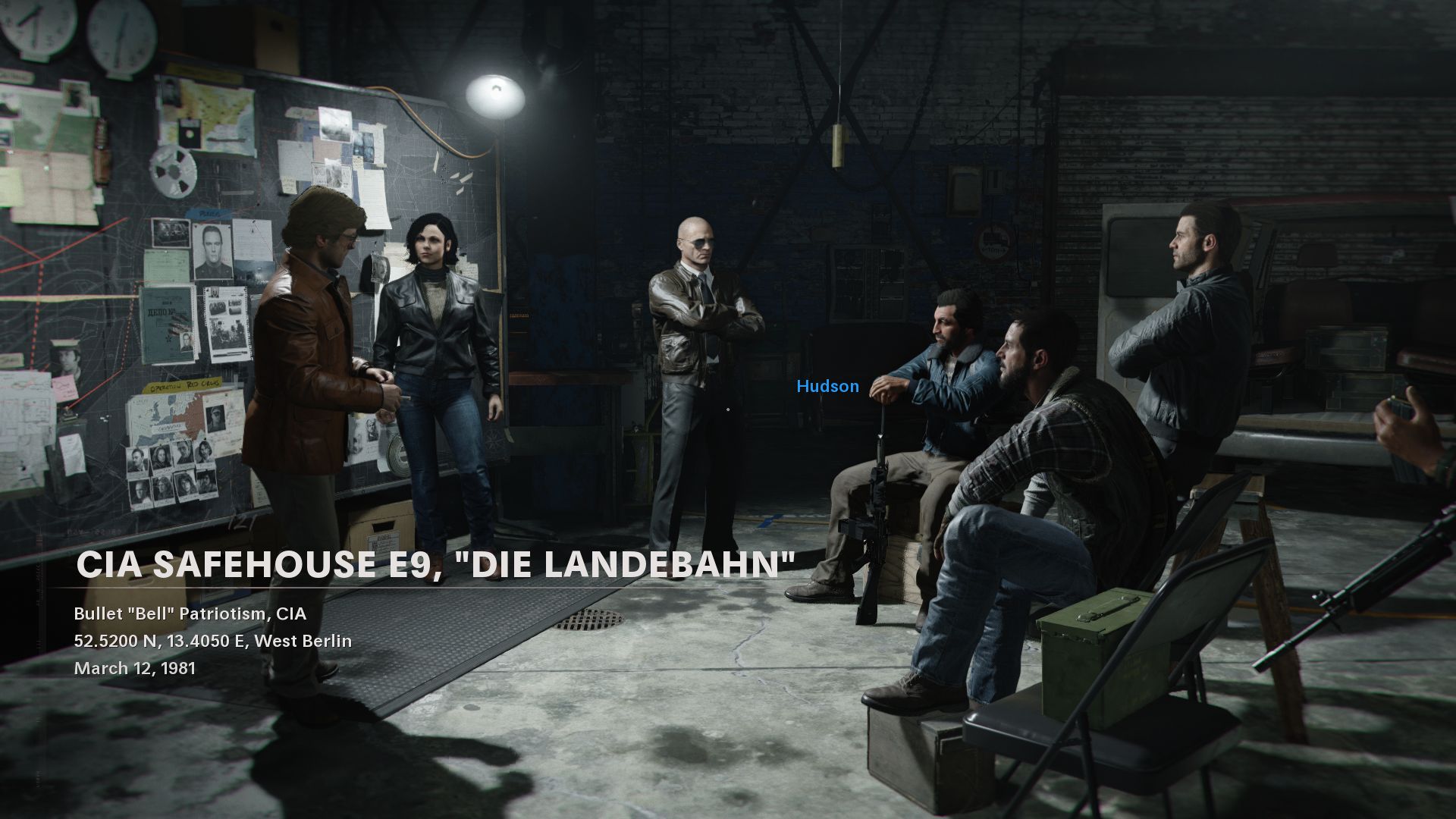

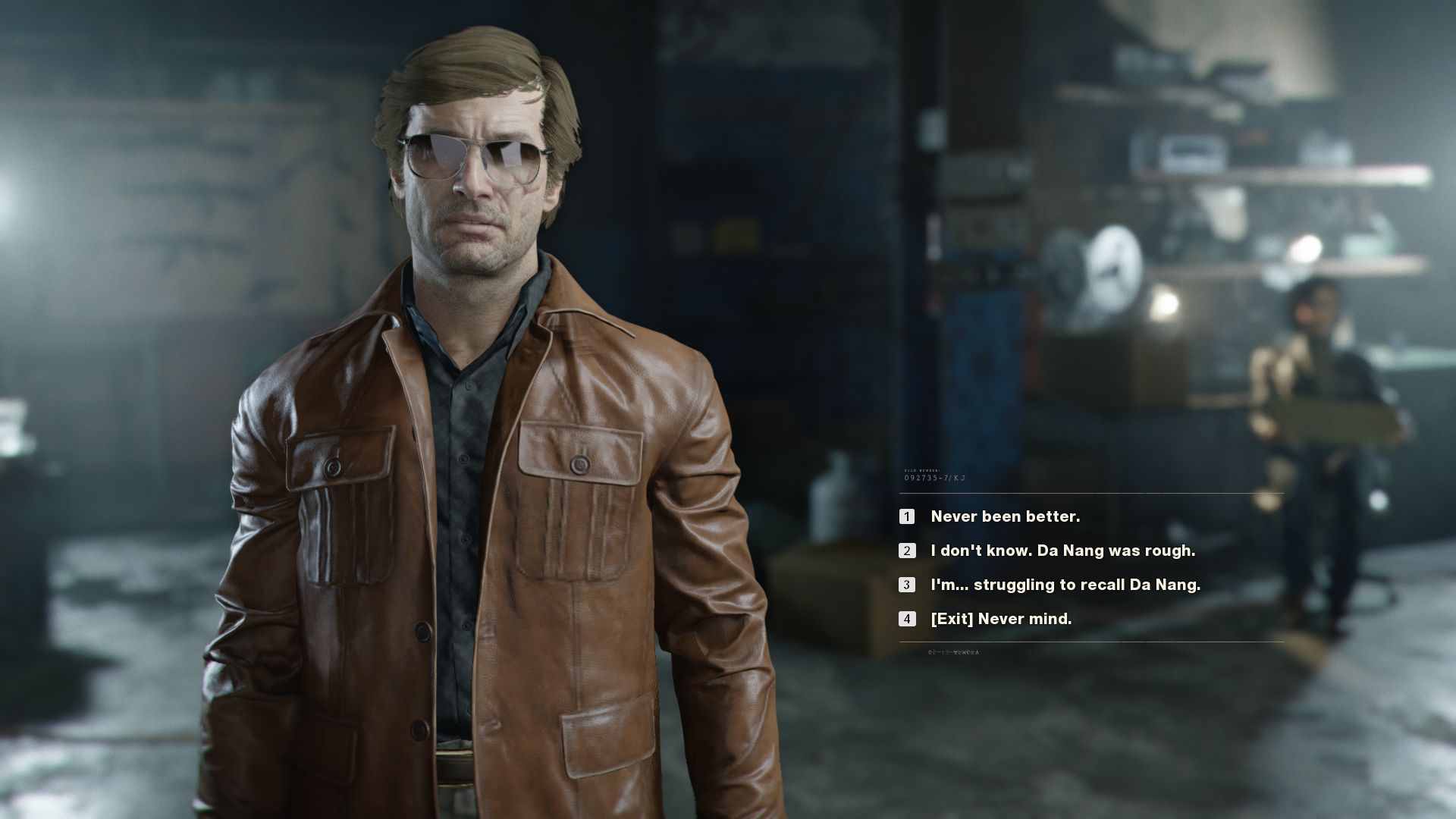

The other person you inhabit goes by the code name “Bell” and you get to fill in their details with a rudimentary character creation screen. Mostly this lets you pick a couple of perks, named for vague psychological quirks. Choosing “violent tendencies” gives you increased damage, for example. My character had “aggressive behaviour” (increased reload speed) and was “calm under pressure” (less flinching when your character is hit). The form also lets you choose skin tone and gender, including a non-binary option that changes the way others address you, using “they” and “them” pronouns in lines of dialogue. I don’t know if this is a step in the right direction or meaningless pandering, but it has invited at least some ridicule for summoning the comical idea of the CIA as a place of both high-profile assassination and socially progressive ideals. Don’t ask me. I just filled in my name as “Bullet Patriotism” and moved on.

In shooter terms, it feels fluid at the fingertips. The peppy SMGs spit their rounds with gusto, the shotguns have heft and impact. Sliding into a room or leaping through a window feels smooth and grants all the feeling of swish power you’d expect from a series that has long completed the refinement of its sense of control. I can’t question the ability of those who worked on the animations or nitty-gritty either. Rooms you might pass with a cursory glance are jammed with details. The neon haze of a bar’s light, the advertisements of Berlin’s U-Bahn. The sound designers in particular need a pat on the back for making it so often possible to tell precisely where an enemy is coming from just by the direction of their cries or footsteps. The echo of the magnum is almost as satisfying as the lingering reverberation of Metro Exodus’ sniper rifle.

Unfortunately, the attention to detail committed to its aural soundscape doesn’t extend to the plot. While Cold War lets you carry out atrocities in the name of big action (napalming villages, gassing enemies, executing surrendering enemies), there is no deeper examination of those atrocities. Some players will argue there doesn’t need to be - this is a stupid action game after all. But living as we do in the hinterlands of the Terror Wars, a time in which the US military recruits young people via Twitch while simultaneously pointing guns at other young people and recording it for laughs on TikTok, I’d argue that a game developer has some responsibility to examine US war criminality beyond exclaiming: “wow these dudes are bad but also gritty and cool”.

It is set in our reality, yet makes no effort to remark on our reality. It only seeks to provide cheap thrills on infinite airport tarmac. Ronald Reagan stoically invokes the concept of the unsung hero, the true American who kills to ensure eternal liberty. COD has long worshipped this ideal; the soldier as a fundamentally noble occupation. Even today it insists on telling you the name of every incidental trooper you look at, their moniker hovering for a moment as your crosshair passes over them - Jackson, Davis, Serio, Gilmore - doubling down on the idea that US soldiers are heroic men who gave their all, and not also war criminals who routinely level entire towns in whatever district of the world merits punching that decade. Just as it rarely engages with the humanity or inhumanity of any of its walking gravestones (Skiver, Erikson, Jones), it does not engage with the legacy, actions or inaction of its lovingly rendered President, who is essentially there for set dressing, looking over his off-leash war dogs with disarming face crinkles and the assenting nod of a proud father. Earlier this year Wasteland 3, for all its faults, at least presented Reagan as a figure of ridicule, and US leaders in general as questionable demagogues. Here, no such attempt at satire or observation is made. CODWAR’s entire cast play their roles with the scowls and grunts of the spec ops boys in Zero Dark Thirty. There are moments where that breaks, and a half-hearted quip emerges. The problem (aside from the jokes not being that funny) is that they are not satirical jabs or wry observations. They are squadbants, there to signal that these hardened killers are just buds, dude. Good bros like your bros. You could be friends with these killers.

It’s predictable too. There are enough familiar sights to fill your Call Of Duty bingo card in the first few hours. The bad dude chasedown, the teamwork snipe, the being captured and tied up, the getting rescued at the last minute, the nuke the baddies have somehow sequestered away in their baddie hole, the multiple choice forking paths that invariably come down to “kill” or “spare”. It asks nothing of you. Shoot as you have always shot. Trust in your fingers, never the voice in your head saying “wait, haven’t I seen this before?” as you witness another kneeling antagonist coolly executed with a bullet to the back of the skull. It is as railroaded as ever, and suffers from the limitations of its interactive theatre (a generous way to describe the modern CODpiece). There is spectacle in abundance, but go off-script and shoot a German border guard from a rooftop when you’re not supposed to and the game will fade to black and put you back at the previous doorway. One mission sees you barge in on a ringleader hiding out in a motel room. Kill his two henchmen but leave the (unarmed) ringleader unshot and the game will kill him anyway, slumping him against the toilet floor as if from sudden cardiac arrest. Any meaning or impact the player might add is neutralised, as if by shouts of “cut” from a single-minded director.

Please recognise, as I hack away with this hatchet, that I’m not suggesting we shouldn’t have our stupid set piece war games. I gleefully used Northrop Grumman fighter jets to shoot down the pilots of fictional countries in Ace Combat 7. I killed a whole bunch of people in The Division 2 under the orders of another cruel president. I enjoyed these games despite the collar-tugging inference of justifiable militarism. But CODBLOPS: Cold War doesn’t reach the levels of self-awareness required to overpower its poor taste. It feels written to justify the actions of ruthless men and doesn’t offer the most basic character development required to give its deathsquad the benefit of the doubt. As a game, it’s a predictable ride. As a piece of fiction, it is servile. Lead wetworker Adler says in one ending: “Some of us cross the line, to make sure the line is still there in the morning”. The game uncritically reinforces this squalid concept of US foreign policy, arguing it is not only necessary but fun.

CODWAR is happy to peddle this principle to the very end, that it’s handy to have a few psychopaths on the government payroll and call them “unknown soldiers” as a single crocodile tear rolls down your President’s wrinkly CGI cheek. We are explicitly meant to see these men as heroes. Because the alternative to the Black Ops boyz walking in slow motion triumph towards the camera is the annihilation of millions of people and ticking “nuclear explosion” off your COD bingo card. This is the false dichotomy presented by all security services, used by the US in particular to justify torture, imprisonment without trial, extrajudicial killing, and any number of war crimes. To enshrine that flawed dogmatic argument in the form of bad end vs good end is an act of storytelling that is either contemptible, thoughtless, or both.