Throwing off the shackles of a faceless process governing your life is a recurring theme in this blend of sci-fi RPG and interactive fiction, and it makes for a strong rags-to-ramen story of one robot on the run. Even when the game’s own systems of dice and clocks clash with its stories of human interest, it is the people who come out on top.

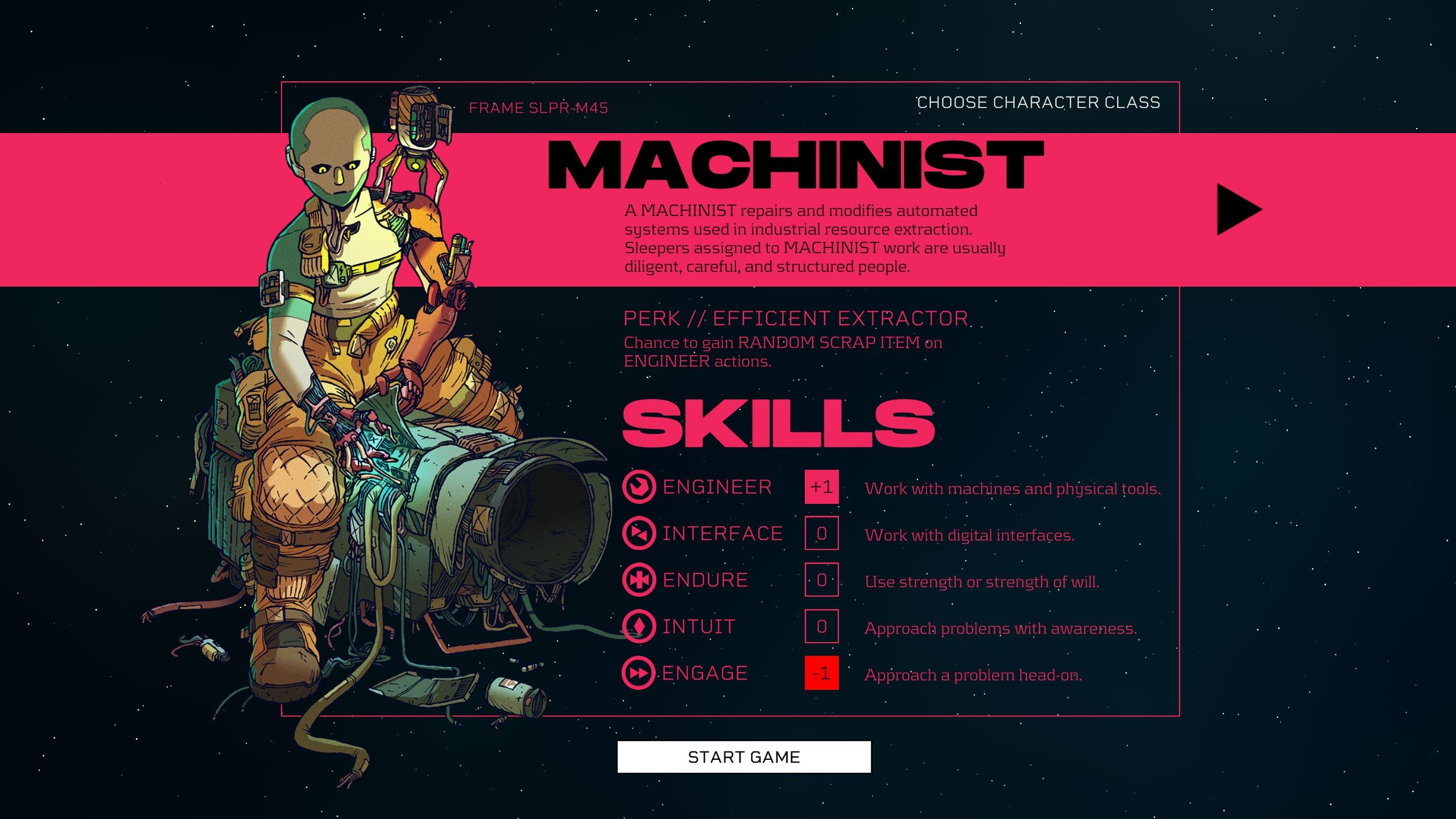

Let’s go over the basics. There are three starting classes. You can be a motor-kicking Machinist, a hardened mining Extractor, or an Operator who likes to hack the planet. Well, not planet. A space station. You arrive as a robotic refugee on Erlin’s Eye, a rotating space station that has seen years of damage and disrepair. Huge chunks of its ring habitat are missing. As an asylum seeker you are here to make a new life of sorts, far from the corporate masters you’ve escaped from. Of course, the company has other plans. Imagine if the laser-cutting protagonist of Hardspace: Shipbreaker did a runner to another solar system while still in tremendous debt, and ended up making friends with a bunch of visual novel characters.

Citizen Sleeper isn’t really a visual novel, but it borrows from that template as much as it does the RPG. Or maybe it could be called “turn-based storytelling”. That means meters. You’ve got a health bar showing your deteriorating condition (the corp who built you did it with planned obsolescence in mind). You’ve got some dice to roll that determine the outcome of certain events (if you’re in bad shape you get fewer dice). And you’ve got an energy meter to keep up, lest you starve. In this universe, even robots need noodles.

You spend each day (or “cycle”) bouncing around a pretty 3D map of the station, doing jobs, meeting folks, and trading “chits” for the robo-insulin you need to stay alive. The dice limit how much you can do in a day, while little clocks count down all around, showing you other possibilities. How many cycles until a scrap ship will dock, or the countdown to the day on which that dirtbag bounty hunter expects another backhander for not turning you in.

New places to visit are unlocked by spending time (and dice) in hub zones. People-watching in the Rotunda might unlock a new bar where you can buy cheap rations. Working a few shifts hauling crates in the shipyard will open up the dock’s assembly line where a better job awaits, alongside some new friends. The map expands, cycle by cycle, turn by turn, adding more and more choices, more places to spend your time.

There’s also a cyberworld into which you can dip, where dice function in a slightly different way. Here, you match dice to various nodes to unlock keys or encrypted data. It’s a clean and straightforward way of letting the player use up the low-numbered dice they might be afraid to spend on a risky action in the real world. This monochrome networld is also the place you encounter the Hunter, a creepy police cyberbeing with tentacles for heads and a doglike body. The Hunter periodically shows up to interrupt your hacking and mark you for deletion. He’s a good boy. A good, terrifying boy.

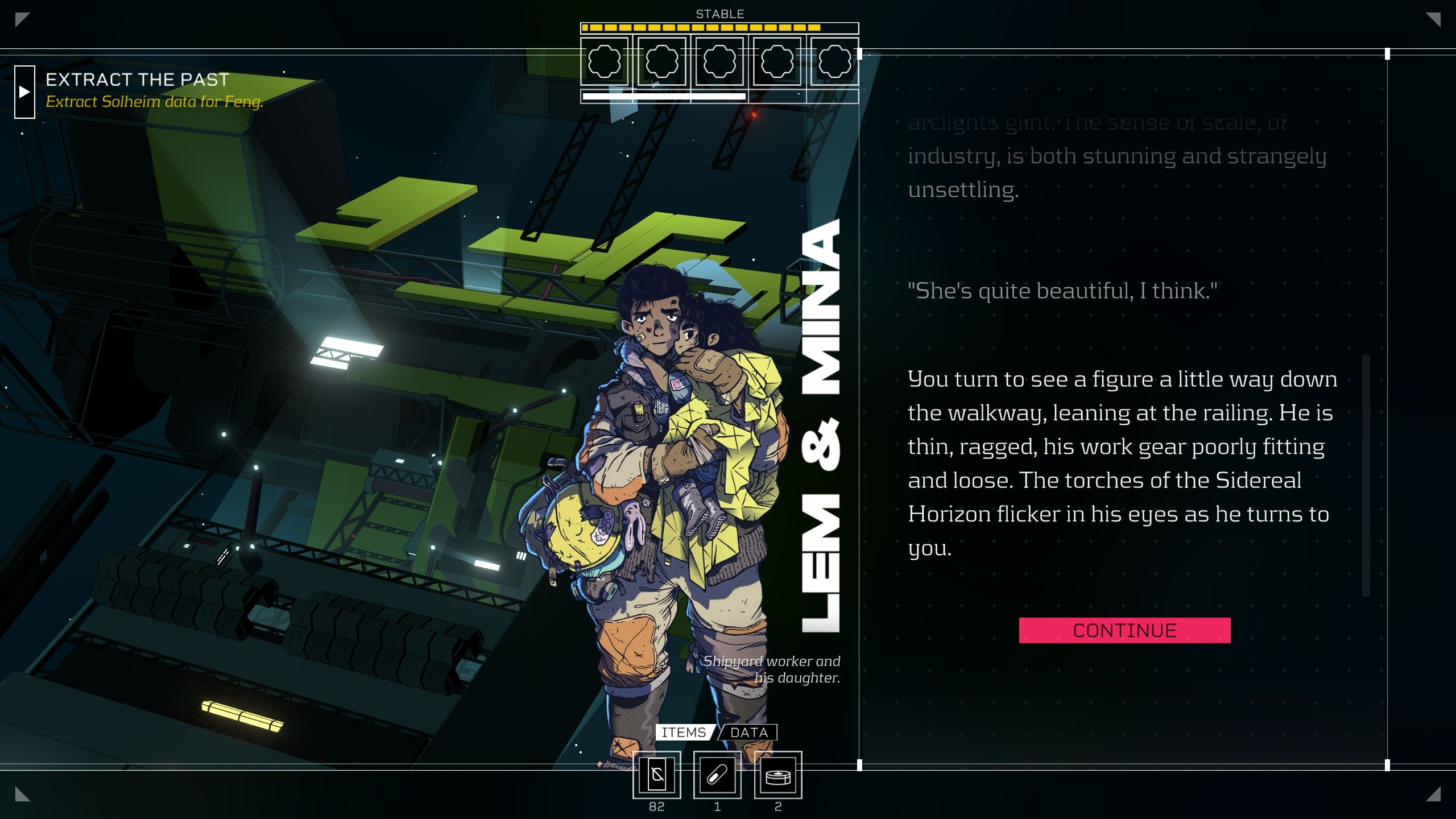

Which brings me to the look and style of the game, which is as cool as a box of cool tools. The character art is detailed and vibrant, often bathed in the hues of some off-screen atmospheric light. The UI is a pretty sci-fi affair, all hard-edged fonts, minimalist colour-coding and circuit board angles. Fans of Alien Isolation’s crunchy UI and geometric symbols will appreciate the effort. It looks great, except in moments where the background model of the space station shines brightly behind some yellow or white text, making it hard to read certain labels or descriptions. But you can just spin your view around, so it never feels truly obscured.

I’ve spoken mostly about the way it functions, rather than the people you’ll meet, because I don’t want to spoil your first jaunt through the ring’s alleys. The space station is overwhelmingly host to gentle folks, sympathetic faces. With the exception of a few antagonistic scumbags, the humans of the Eye are mostly kind, even if their complexities sometimes suggest darker secrets. The future here is not a utopian ideal but plenty still fight for one. People are not cruel, but circumstances often are. It’s a part-tragic and part-hopeful place.

It reminds me of Lancer, a pen and paper RPG where conflict simmers even when Earth has figured out how to feed everyone. In Citizen Sleeper, the space station exists away from the megacorps who run amok in the galaxy. But inequality is a weed. Factions stew. Hardship is rife. This is not a classic dystopian land of cyberpunk corpo-values, nor a Star Trek style universe with a menu of unusual global cultures. Instead, you get a kind of space ruin on the edge. A post-disaster Startopia where workers struggle on a daily basis, and hypercapitalist enterprises threaten to self-revive on the very station they once abandoned without a care. The Eye is a scrappy place, and not just because of the scrapyards.

Which could also be my polite way of saying there are bugs. There are a lot of typos too (at least in my press build) and characters will sometimes explain things you’ve already experienced as if they are news to you. Quests are multi-tiered and sometimes go on longer than feels necessary. For example, Feng, that vengeful man from IT, has a long quest of corpo-purging that I was following solely for ulterior motives (he said he’d remove a tracking bug from my cyberbod). Every time he explained an extra step in his plan, I wanted to write a third dialogue option over the screen that read: “I’ve done enough! Debug me already.”

There are also moments of what I like to call “punching the reporter”, a common pitfall in interactive fiction, where tersely described dialogue choices lead to unexpected results. During the outbreak of a riot, for example, I was talking to a workmate, trying to get his attention. One of my on-screen choices was to “leave alone”, which I read as “don’t speak to him anymore” (i.e. leave it alone, drop the subject, stop pestering). Of course, “leave alone” actually meant to physically leave the location, to leave this person by himself. As a result, I abandoned my friend to his fate in the ensuing unrest. Whoops. Whether this was an unfortunate subtlety of the English language or my own bad comprehension skills, it nevertheless spoiled a tense moment in one of the more heartfelt quests. (Did I mention I proofread games now? Hire me! I’m broke).

The game loses some heart in the odd times when no character events are firing and several cycles in a row pass without much colour. In this dry time you interact solely with the systems of push and pull underlying everything, levers of number-bumping and clock-tweaking. This is a weakness of systems-driven storytelling in general, the feeling that a story can be “gamed”. There is often a point in works like this, when narrative is welded fast to numbers, where the story peels away and you end up pressing buttons speedily, ignoring the flavour text in menus because it is the system now telling the story, not the narrator.

Citizen Sleeper is not the worst offender for this, but it doesn’t escape the trap completely. There were periods in which I zipped through cycles, feeling less impelled by the story of a self-driving personbot than by the grander machine underneath it all - the inventory swapping, the resource management, the clocks and meters that my borked human mind desires to see filled and blinking.

Luckily, it’s easy to fill in cog-heavy blanks in the story when a game is this flavourful and atmospheric. (Quick shout out to the music. The character artist has drawn a studious lo-fi beats robot and you can probably summon an accurate idea of the game’s music from this image alone). Some of my favourite interactive fiction drops you into a world without over-explaining it (see With Those We Love Alive; see Horse Master, and then never unsee). Don’t get me wrong, Citizen Sleeper isn’t as esoteric as a superpink Porpentine potboiler, but it isn’t as straight-talking as Neo Cab or The Yawhg either. Its closest comparison in tone might be the minimal transhumanist tour of the solar system in Sun Dogs.

If you recognise and enjoy any of the choice buffets I’ve just listed, you’ll probably like Citizen Sleeper. It has the feeling of playing through a Lancer sidestory without any of the convoluted hex-tile mech rules that make that tabletop RPG daunting for anyone who yearns for rules-lite role playing. Not bad for a game that was at least partially conceived to dull the pain of having sea urchin spines removed from the lead developer’s foot.

I don’t know how it holds up on a second playthrough, but I’m eager to find out. There was an entire farming community called the Greenway which I never even entered, a wasteland of scrap I never had the stats to explore, and a bunch of wiry characters whose storylines I did not delve into beyond a first meeting. I consciously left these areas aside, like reservedly eating only half your bag of sweets in the cinema, so you can have cola bottles for breakfast tomorrow.

Towards the end of my playthrough (probably eight hours) it became clear I was about to embark on a long overstars journey. The flavour of the world was enough to make me spend my last cycles working to save up a bag full of chit-monies and a stash of robodrugs. I did this even though I knew the ending sequence would roll as soon as I left for realms unknown. Mechanically, I could have slept for my last five turns. Or investigated a few characters I’d left waiting. Instead, I pushed buttons and pulled levers to get items I knew I would never use, that I would neither drag nor drop, purely out of a desire to not break character, to have my last few cycles fit the story I was building.

The fact I was invested enough to do this says everything about how attached I became to the denizens of this crumbling station, how invested I became in my role. It is not a perfect game but it has enough player freedom and likeable characters to earn my commitment to the bit. Which is the exact strength of a good tabletop RPG. Ultimately, it’s not the machinery of Citizen Sleeper I’ll remember, not the ticking clocks and the rerolls, but the hackers and the mercs, the drunks and the shipyard workers. Because like Feng once said: systems aren’t important, people are.