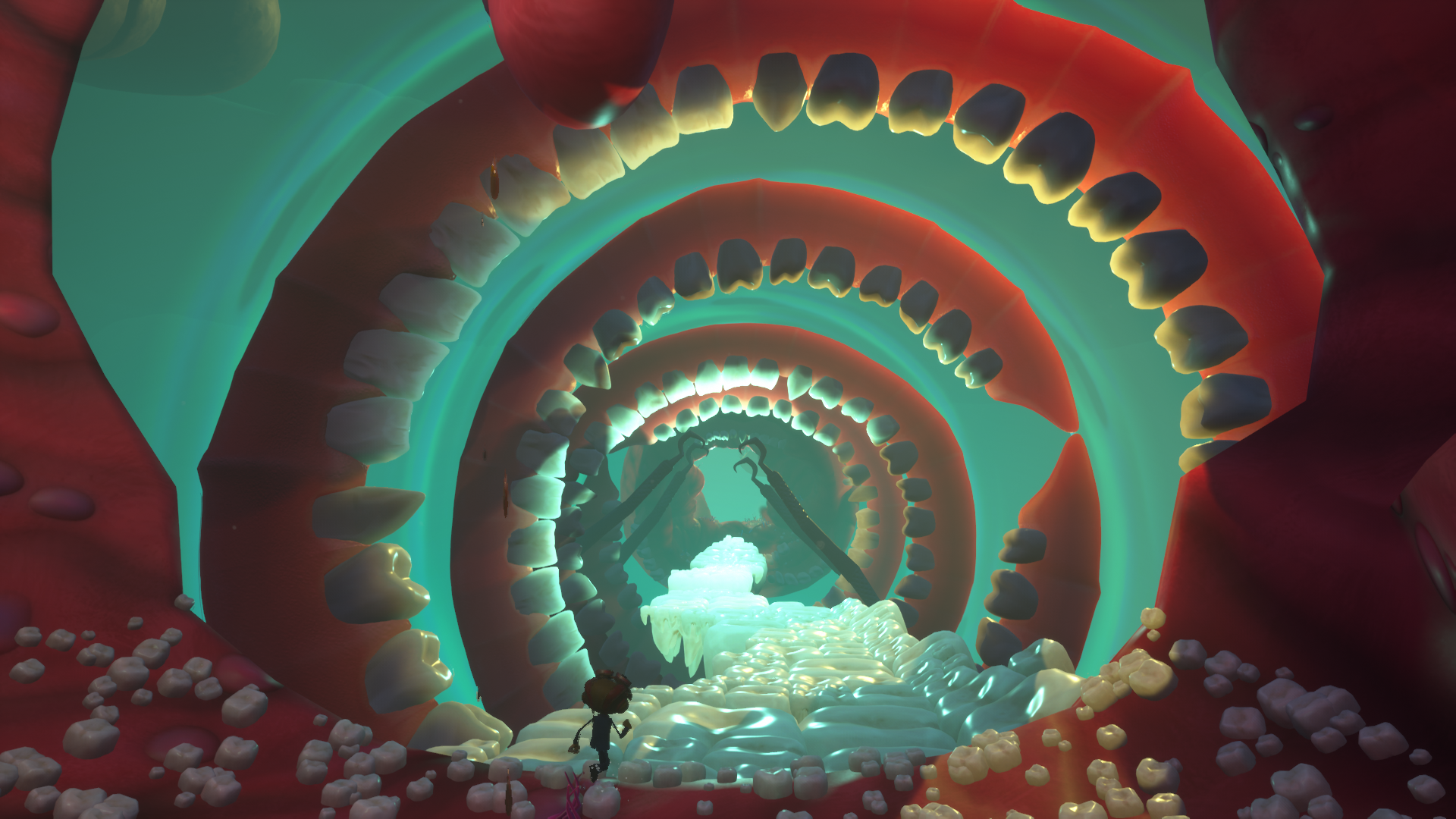

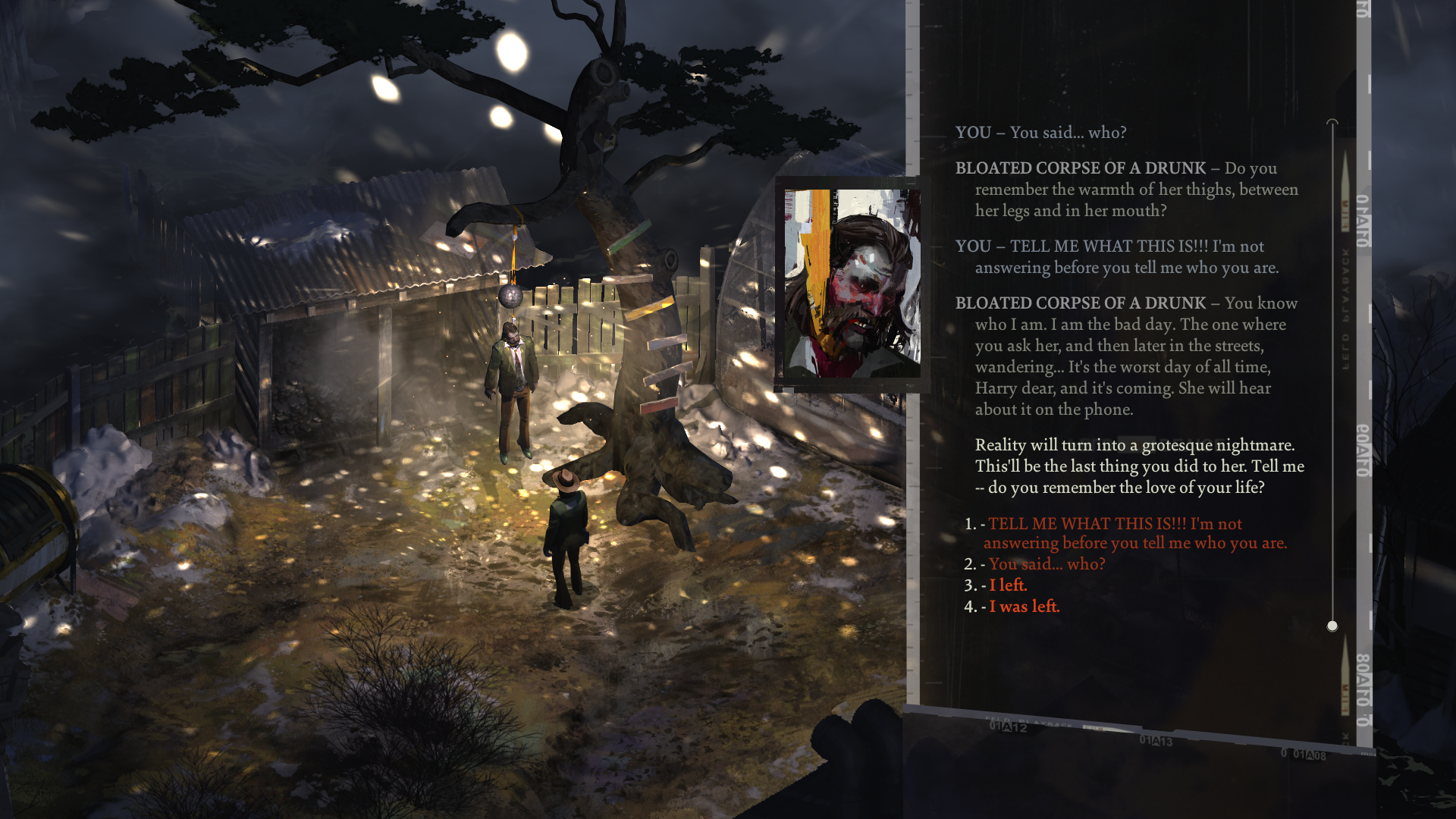

These individual realities can only be conveyed through language and other subjective means of communication, and more and more games are grasping this fact, turning inward to explore and map the inland empires of the mind. They have all the tools of the medium at their disposal to turn the invisible workings of the mind into landscapes of audio-visual and mechanical metaphors that can be explored and interacted with. At their best, they convey the dynamic and complex mechanisms of the psyche in a way that only this medium can. In Psychonauts 2, we follow the young psychic agent/intern Raz on his excursions into the human mind. Using a Psycho-Portal which can be attached to a subject’s head, Raz projects himself into the confused unconsciousness of colleagues, mentors, and antagonists. Each mind we explore is a whimsical yet chaotic and treacherous stage on which mental processes are being played out. They are intricate, self-contained platforming worlds full of secrets and idiosyncrasies to be dealt with, each with its own messy tangle of free associations, symbols, and metaphors that express the preoccupations and struggles of a mind. Our goal is (usually) therapeutic; using all the tools of platforming games, we navigate and explore the mind to gain understanding, sort out emotional baggage, and fight off doubts, regrets, and anxiety attacks in the shape of pesky enemies. Take one of my favourite stages, Compton’s Cookoff. Compton Boole, a friend to animals and one of the original psychonauts, seems to be struggling with anxiety and sensory overload when we meet him in voluntary psychoisolation. Diving into his mind, Raz and an aspect of Boole find themselves in a nightmarish cooking show called Ram It Down, with some of Boole’s colleagues as cruel judges. Since Boole is completely overwhelmed by the pressure, Raz needs to help him complete the tasks within an increasingly tight and stressful time limit. The genius of it is that, without spelling it out for us, Compton’s Cookoff not only conveys Boole’s poor self-esteem, his performance anxiety, his fear of judgement and rejection from his peers; it also makes us participate in them and experience them first-hand through audio-visual overstimulation and stressful timed challenges without giving you the time to familiarise yourself with the layout and mechanics of the chaotic set. Each stage is designed to express the psychological struggles of the person it belongs to. Ford Cruller, for example, has buried the grief and guilt of an old trauma beneath seemingly random preoccupations with bowling, sorting mail and hairdressing. His trauma betrays itself by twisting these innocuous activities into strange and dark symbols of war, chaos, and transience. In Cruller’s Correspondence, a chaotic and infernal post office, one of our tasks is to find the missing keys of a typewriter, then address the letter in it to someone dear to Cruller by jump-stomping the correct keys. That someone is, of course, Lucrecia Mux (aka Maligula), whose name and memory Cruller has repressed. If you pay close enough attention, you’ll also see he used to address her as Lucy, not Lucrecia. The puzzle is simple, but effective. It conveys a lot about Cruller’s psyche: the disarray within his mind, his regrets over a letter he should have sent, but didn’t, the intimacy he shared with Lucy, the pain caused by her name and his wish to forget. Meanwhile, in Bob’s Bottles, botanist Bob Zanotto finds himself stranded on a lonely island in what is – presumably – an ocean of booze. Bob struggles with depression-induced loneliness and alcoholism, and his mind is a drowned world. The fluids symbolise both his disconnection from others, but also (as water) the potential to regrow the seeds of his neglected friendships. Sailing the seas of Bob’s psyche, we discover other islands: entire regions of himself from which Bob has withdrawn. Through our exploration, we create a topography of Bob’s mind, demonstrating that his mind is a coherent whole, not an isolated fleck lost in the ocean. Once we bring back the seeds we have recovered from these distant parts, they sprout into distorted and terrifying versions of Bob’s lost husband Helmut, his mother and his nephew. Throughout the ensuing boss battle, Bob is wrapped in a protective cocoon: the end goal is not to defeat the monstrosities Helmut has created in his mind, but to break the cocoon and make Bob realise there’s nothing to be afraid of. By using the tools of platforming games to allow us to directly engage with visual metaphors for mental processes, Psychonauts 2 turns the mind into a strange and dangerous, but ultimately understandable and healable place. Our goal is always to discover and gain understanding, to open up connections and put things together again. Even the fighting is framed as either defending the mind from its own demons, or breaking down barriers that hide and obstruct, rather than as an act of aggression. Psychonauts 2 is far from the only game that tries to turn the mind inside-out, and there’s more than one way to do so. Take the RPG Disco Elysium, where instead of whimsical landscapes, the mind is presented as a cacophony of inner voices. These voices - all aspects of Harry’s psyche - interject throughout the game’s many dialogues, vying for Harry’s attention, drawing him into arguments and often encouraging self-destructive behaviour. Unlike in Psychonauts 2, our aim isn’t to heal Harry. All we can do is influence the ways in which he attempts to cope with his perceived and real failures, his addiction and self-loathing, by navigating his internal dialogues. The action-adventure Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice, on the other hand, is an exploration of schizophrenia and trauma that relies on artful audio-visual effects to convey the perception, experiences, and inner struggles of Senua, a Pictish woman in the Viking age. In another point of contrast to Psychonauts 2, Hellblade is less about looking at mental illness, and more about looking through it. Senua hears disembodied voices all around her, perceives meaningful patterns in random constellations of objects, speaks to phantoms of her dead lover and suffers through dreadful visions of death, decay, and demonic assailants. Presenting the world through the eyes of a person suffering from schizophrenia, Hellblade makes no distinction whatsoever between an objective outward realm and a subjective inward realm: everything Senua experiences is, as far as we are concerned, equally real. Psychonauts 2, Disco Elysium and Hellblade differ wildly, ranging from whimsical comedy to psychological horror, from platformer to CRPG. And yet, they all reach deep into the toolboxes available to their respective genre to turn the mind inside out, letting it spill out into the open. In a world that still all too often dismisses mental illness as something less than real, and working from within an often literal-minded and materialistic medium, games like Psychonauts 2 do something important. They bring together empathy and wild imagination to throw a metaphorical light into metaphorical dark corners. Sometimes, you need to make stuff up to get at something real.