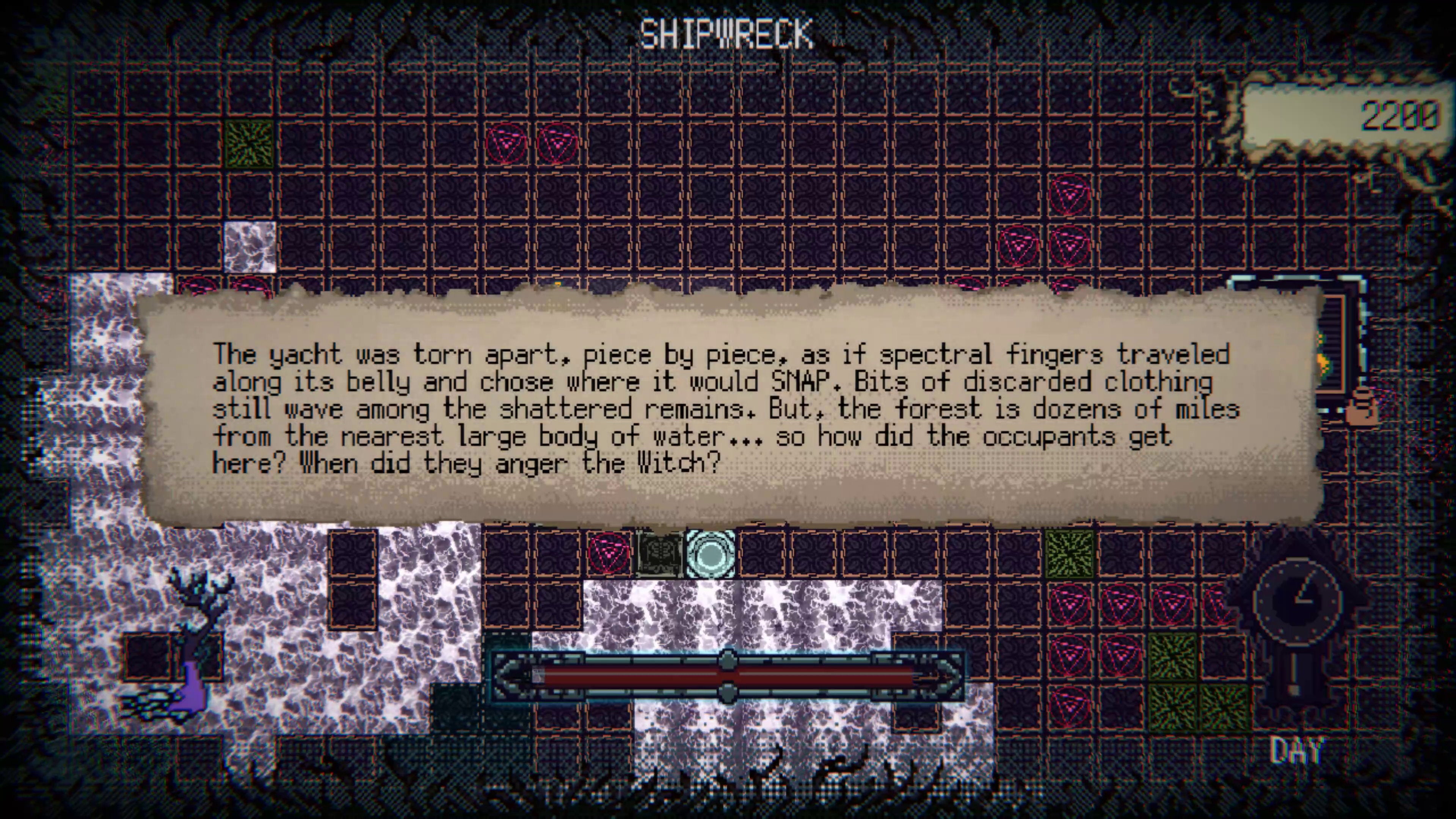

That’s right. Taking cues from Hideo Kojima’s hiking postal sim Death Stranding, Witch Strandings is a game that not only asks what Sam Bridges’ cross-country cargo routes might look like if they were made with a fraction of Kojima’s development budget, but also how games can create experiences that are “larger than my screen,” says Nelson Jr. And the answer, it turns out, lies in your PC’s humble mouse. Born from “a variety of wild-eyed, noodle-armed rantings that came from this idea of an interface game that extends beyond the borders of your screen,” Witch Strandings is a game where you play as a spirit who’s been tasked with nursing a cursed forest back to life again. Not only must you cleanse the land of a terrible hex put there by its titular witch, but you must also help its local creatures overcome a myriad of different afflictions. Some are sick, hungry or thirsty, others are injured or, more worryingly, ‘disturbed’. Many are a combination of all these things. Thankfully, you can cure them of their ills for a day or two by delivering certain items to them found in other parts of the forest. Their favourite food, for example, or a comforting blanket. To get to these places, though, you’ll need to blot out that pesky, miasmic hex with, and I quote, “haunted mycelium”, expunging the life-zapping tiles bit by bit to help make your route through the world a little bit easier. Think Death Stranding’s ladders, bridges and ziplines, but as supernatural shrooms. Only you aren’t navigating this world with a keyboard or a controller. Instead, the only way to move your spectral ball of light through its forest of gridded squares is to swipe, push and nudge your mouse where you want to go. Large sweeps will see you leap across the screen, for example, while gentle brushes will only move you a square or two. However, when your vision is limited to just a handful of squares in front of you, it’s easy to find yourself trapped in one of its poisonous bogs or tangle of thornbushes if you rush in too quickly. As such, it pays to go slow and steady when you’re pushing out into new, unknown areas, and you can finetune your mouse’s sensitivity settings to give smaller bumps and prods on your mouse mat a real sense of careful, cautious resistance. It’s an idea that comes from Nelson Jr’s intense love of unique gaming experiences, a point he further illustrates by shifting our conversation to Bend Studio’s Resistance: Retribution, a third-person shooter that came out on Sony’s PlayStation Portable back in 2009. “The developers were tasked with somehow fitting this big budget AAA FPS franchise onto a portable handheld device. How do you do that, especially when this device lacks a right stick? Their solution ends up being that you [use the face buttons to] move the camera in cardinal directions,” he explains. “The very first thing that went to my mind was, ‘Oh this is bad.” But the second thing was, ‘This can only exist because of this constraint. I would love to play another game like this’.” As such, Witch Strandings is one of those increasingly rare things on PC: a platform exclusive. There are no plans to add in keyboard support, for example, or make it playable on a controller. To his credit, though, when I ask Nelson Jr about whether this decision makes good business sense for an indie studio in today’s climate - the going consensus being that most developers want to get their games on as many platforms as possible these days - he remains unphased. “I don’t want to make games that are bad,” he says, “but I am increasingly driven by a mania to make games that could be bad - that swing for something artistically, creatively and philosophically distinct that could be a misstep, but, in the process, end up unlocking barriers, and unlocking new glimpses into what our medium could be and the things that we find enjoyable. Which is a very roundabout way of saying that more games are more playable in more places than ever these days, and I’m struck by, despite being surrounded by this mountain of material, how rare it is for me to fall utterly in love with a game now. Because they assume that their value comes from being standardised instead of relating to the controller, the mouse and keyboard, the primal interface we use to interact with things, the foundation of video games, in a distinct way.” Of course, we’ll have to wait and see whether the general gaming public agrees when Witch Strandings eventually launches on PC, but his words still end up striking a bit of a chord with me. Sure, Death Stranding may not be doing anything as eccentric as only letting you move through its world with a mouse, but part of its enduring appeal for me is how deeply it asks players to engage with its landscape through its rigorous control scheme. There are buttons to help stabilise Sam as he walks, for example, and the ease with which he’s able to move through the world in front of him is determined by both the weight of his cargo and how it’s packed. But the real genius of Death Stranding isn’t necessarily how it controls, Nelson Jr goes on to say. Rather, it’s that its baffling collection of ideas, characters and themes found any kind of audience at all. “It’s not the only game in the world to have logistic factors, for example, or asynchronous multiplayer as we’ve seen in things like Elden Ring,” says Nelson Jr. “But I do believe that Death Stranding, by being such a big budget commitment to a new unifying ideal, provides a focusing rod for a lot of people to describe what they’re making. I am suddenly imagining that a wholesome games developer, for example, trying to convey that their game mainly about moving things from place to place and taking care of people is meaningful, now has Norman Reedus’ toned, naked ass up there saying this is worth investing into, see? Look at the reviews, look at the sales, look at the fact that investment was committed at all. “Ending up being the second Strand-type game and having a form that is so distinct from the original is, I’m interested to see whether that will end up being a unique contribution to the medium that we can make, because it instantly cracks open the idea of what a Strand-type game can be. It doesn’t have to be third person, it doesn’t have to have a giant butt, it doesn’t even have to have game pad type controls. You can’t play this with a game pad. We don’t have that control setup at all, so it would be a fundamentally different game. So the question of what a Strand-type game can be now is entirely up to people’s imaginations.” In fairness, Nelson Jr isn’t sure whether the ‘Strand’ branding will necessarily enter our gaming lexicon in the same way that roguelike or Soulslike has done over recent years, but he’s adamant that it’s only by “questioning the horror of the status quo” that games can move forward as a medium – and in Witch Strandings, the emphasis is very much on the word “horror” here. Believe me, the forest in which you find yourself in is a truly cursed and oppressive place when all’s said and done, from the words used to describe the animals’ predicaments to the game’s wider colour palette: all purples and blacks and bioluminescent blues. It’s an image that’s not too far removed from Kojima’s oil-slicked world in Death Stranding, but Nelson Jr tells me it wasn’t always like this. Indeed, as he reads out some of Witch Strandings’ earliest design ideas to me, he paints an altogether more positive picture of potential wells his Strand-type game could have drawn from: “One of them was a muse for a commune of artists, so you’re invisibly affecting this commune of artists,” he says. “There was a child in a rural setting, such as Coraline, and taking care of magical creatures only you could see; a spirit in hell comforting abandoned souls; nurturing abandoned electronics on a planet; nurturing the internal components of a computer; a direct biblical parable of where you’re like feeding sheep and flocks; an XCP control-like game taking care of anomalies in a facility…” But then: “In very big letters I have at the top of this list, and the last thing that was added, was DARK FOREST, magic realist Ghibli vibes, dark things live in the woods and you’re not one of them.” Of course, it was this final idea that eventually won out with Witch Strandings, but when I asked him whether Strand-type games needed this kind of drastic, apocalyptic-type setting in order for its ideas of nurture and restoration to really sing, he does agree that “more game genres would benefit from a sense of despair”. We’ve become so used to the world ending, he says, that “we don’t bat our eyelash at an apocalypse” now, so “having a setting that also allows the player to live in a place where suffering is commonplace, and then make their business to see that status quo change is uniquely fascinating and empowering in a way that I believe a lot of games’ apocalyptic fiction has not explored yet.” As that old saying goes, though, that kind of power also comes with great responsibility, and Nelson Jr isn’t going to let players who abuse it in Witch Strandings off the hook. Without straying too far into spoiler territory, your main marker of success in Witch Strandings is the number of points you accumulate by doing good deeds. About an hour in, however, you acquire an item that lets you remove its animal folk from the game permanently, effectively murdering them in cold blood. You don’t have to use it you don’t want to, but if you do decide to go through with it, “your score suddenly looks weird,” says Nelson Jr. “It never fully recovers. No matter how much you work to balance that ledger, people can see the scar, even in any screenshot that you post. […] I think that’s one of the ways that we can use the language of video games in a way that is unique to the medium - and sustainable for a small team to build - to do something a little bit weird and different.” Indeed, I’m keen to see what kind of mark Witch Strandings will make on this budding ‘Strand-type’ landscape when it eventually arrives on PC – which Nelson Jr assures me is soon, despite not being able to name a date just yet. Still, whatever happens, I get the feeling that this is by no means the weirdest thing Strange Scaffold have up its sleeve at the moment - nor its greatest potential misfire. “One of the games that we’re making at Strange Scaffold right now, the primary mechanic is that you play shuffleboard on a Mario Golf power meter, using an action wheel inspired by the Oblivion persuasion mini-game. Which is to say, I’m in completely uncharted waters off the sea and have no perspective for what is a misstep or not,” Nelson Jr says laughing. “Before Space Warlord Organ Trading Simulator was publicly unveiled, my mom was, ‘Oh, are you sure you should make this? I’m not sure this is a good idea.’ And then it turned out really, really well and she also really liked it, so I hold this over her now. The Organ Trading Simulator worked, so why not the game where you play shuffleboard on the Mario Golf power meter using the Oblivion persuasion wheel?”