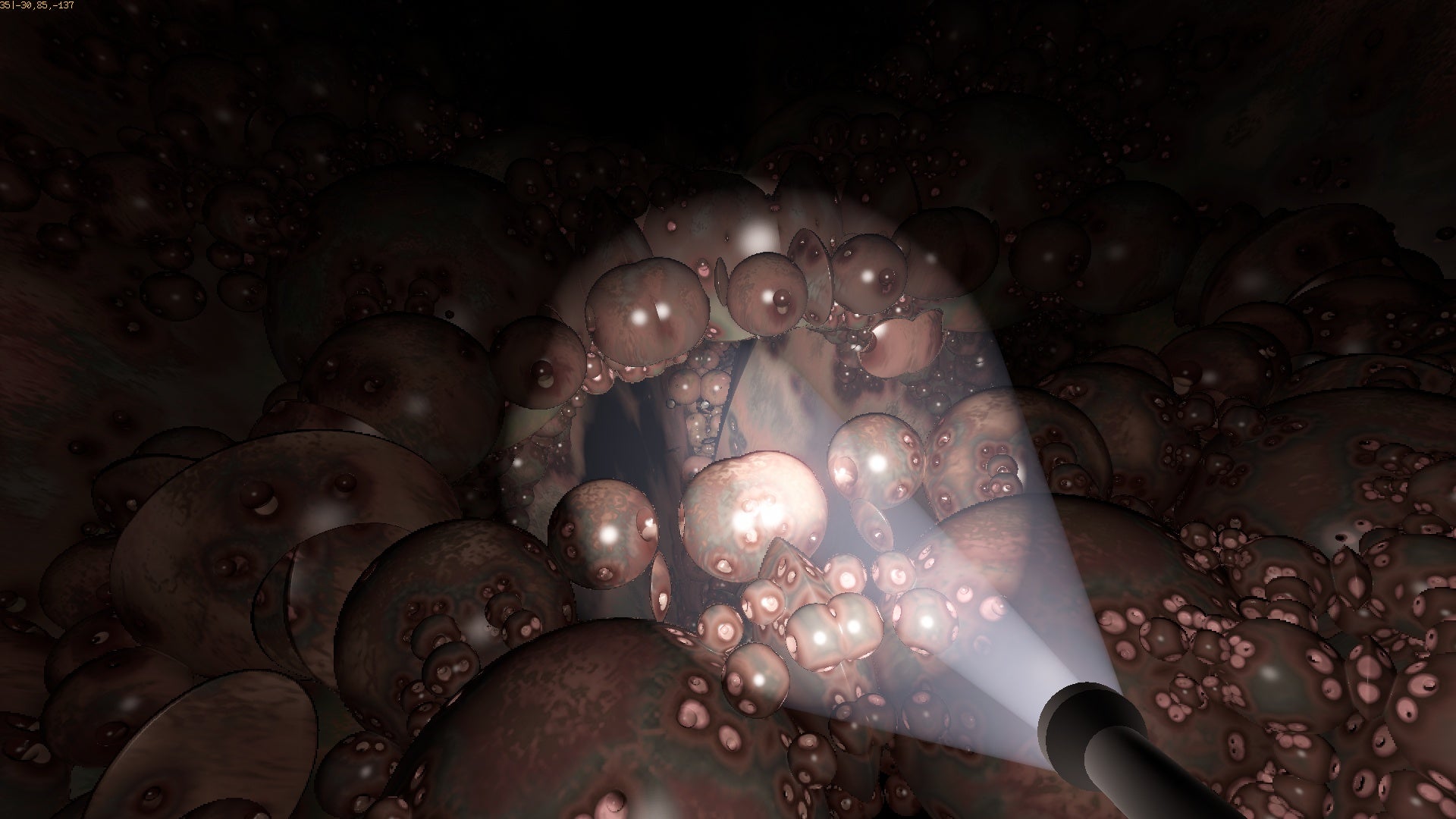

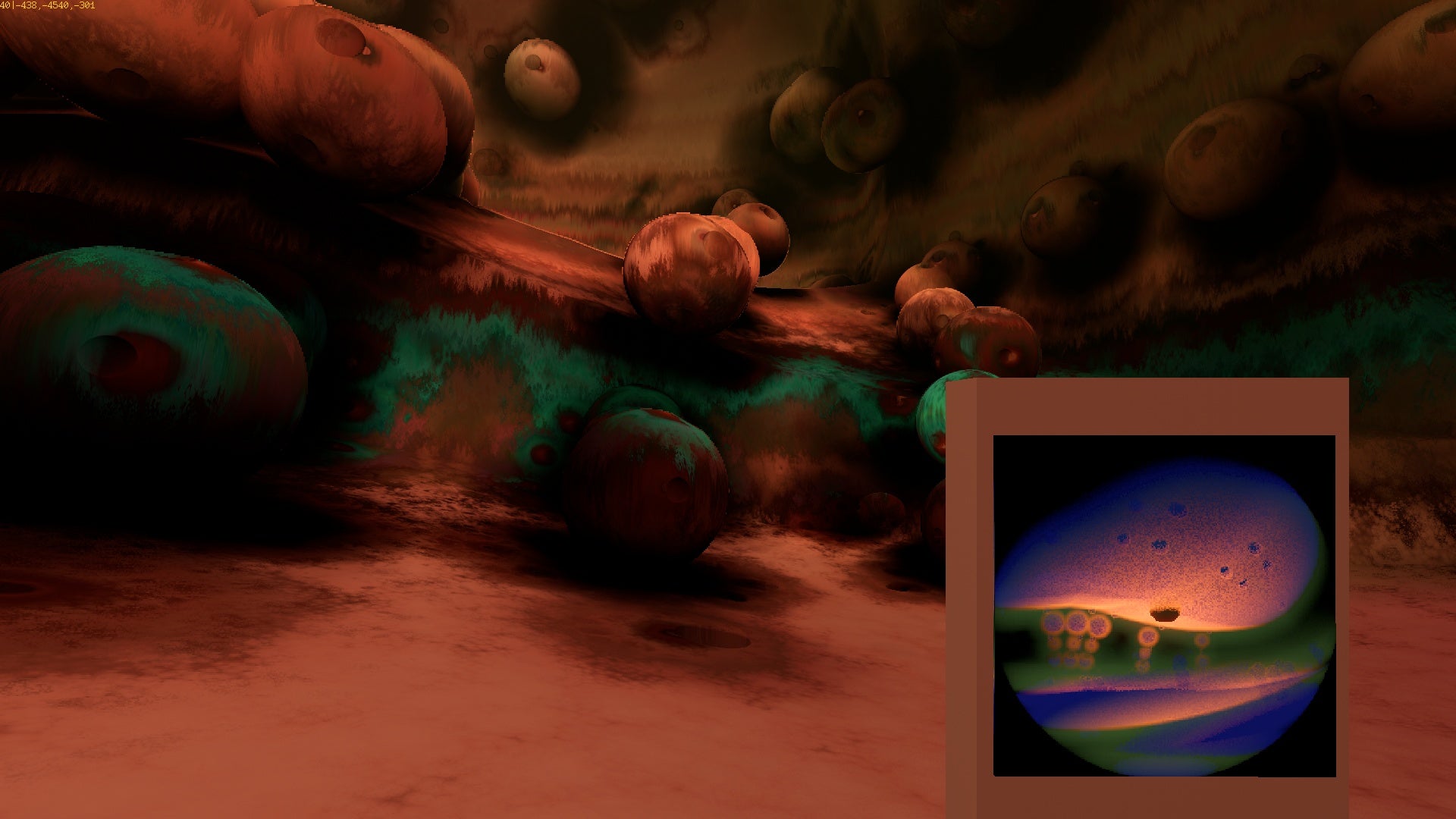

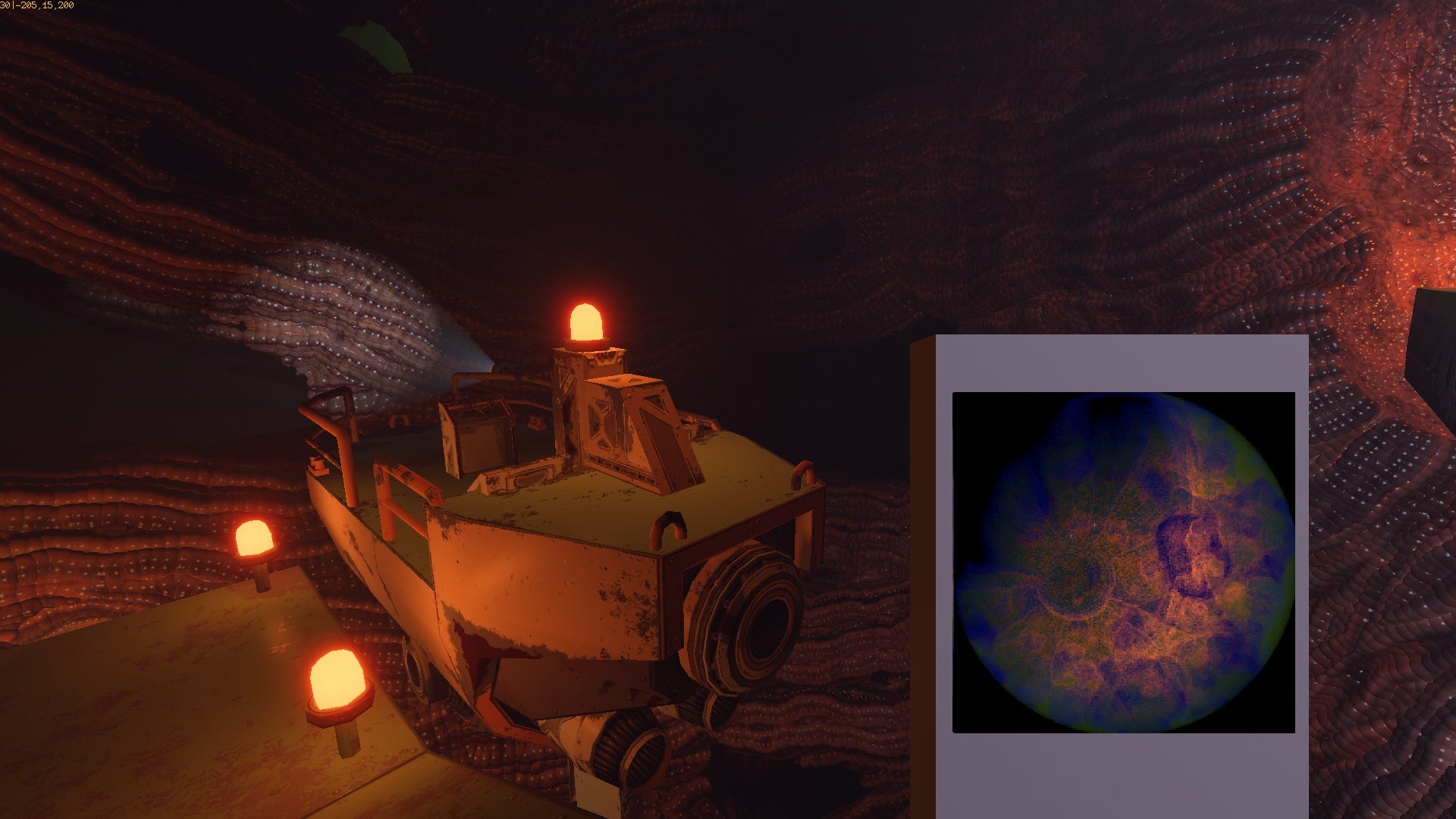

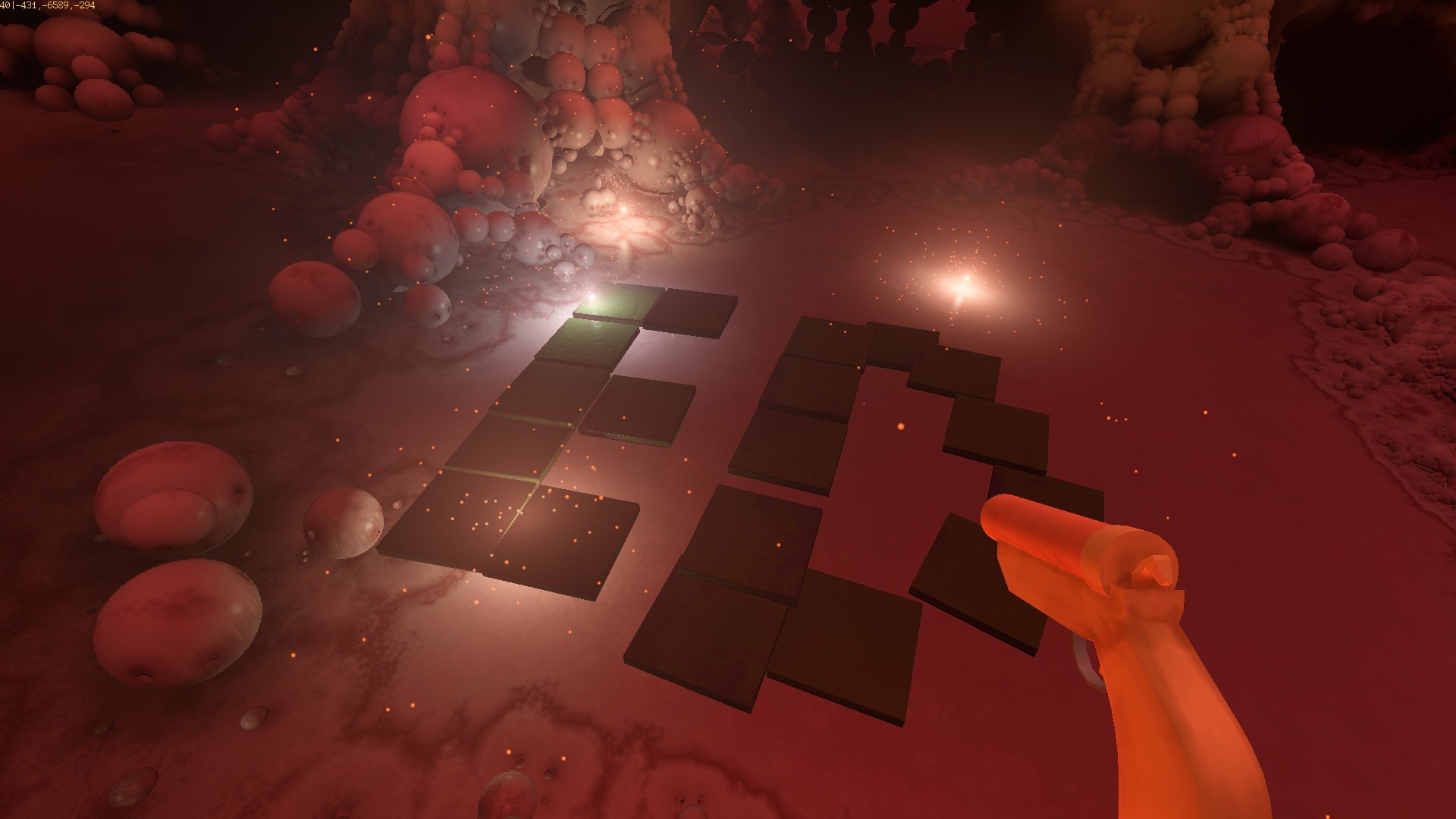

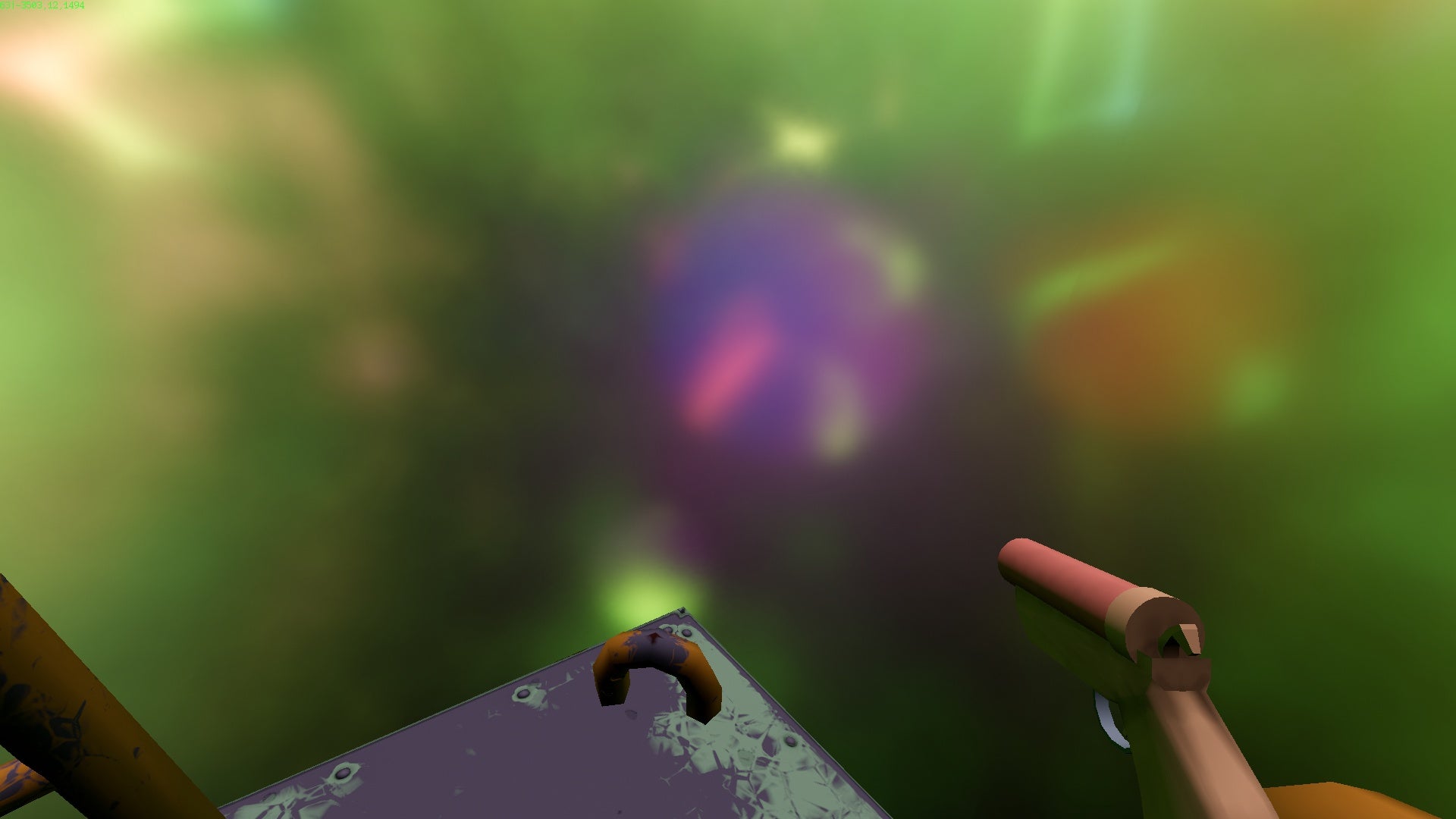

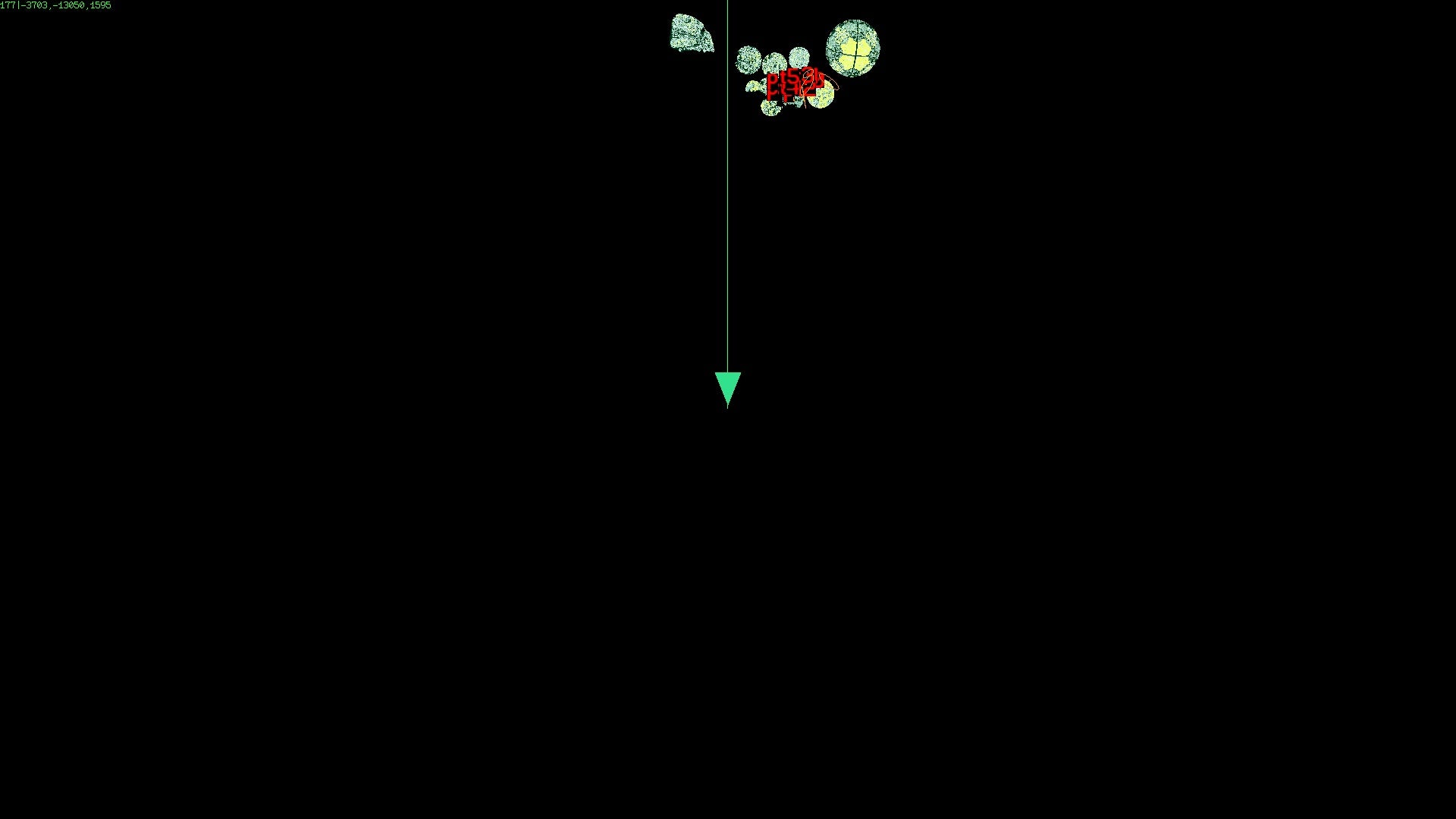

For the best part of a minute I fell - through coloured light and a confusion of curving distances, the thudding of my ship’s engine melting into the mists above. The worst thing about falling in Yedoma Globula is the sound. There is none. No air screaming past your ears, no rattle of loose cloth or equipment. Touching down, you brace for the crunch of bone but it’s as gentle as a bubble meeting water. This being a work-in-progress game with an early build on Itch, it feels like the force of impact isn’t so much absent as deferred, waiting to be inflicted by an update – all those fatal tumbles catching up with you simultaneously in a liquefying spacetime implosion. Dusting myself off, I found myself on a vast plane. Far away, the floor sloped up into fog. A little nearer lay angular drifts of symmetrical orbs, some big enough to stand on, others glinting flecks like drops of ocean spray. Checking my map, a 3D wireframe apparatus redolent of the Homeworld series, I saw that I’d fallen beneath the cluster of so-called “biomes” the game’s Russian creator, Bananaft, has mapped out for visitors. Perhaps this is it, I thought to myself - the bedrock of this strange, imponderable universe. But then something occurred to me. Among Yedoma Globula’s handful of spelunking tools is an energy ball launcher that leaves short-lived craters, the edges sucking back together after a couple of seconds. I’d used it like a machete to widen gaps and slice through fussier bits of free-floating geometry. But what if I used it like a drill? I experimented with blowing holes directly underfoot and found that, with reasonably careful timing, I could burrow deeper and deeper before the ground filled in. The surface sealed itself overhead as I gouged and blasted. I swallowed my claustrophobia and kept digging. Each flash of detonation revealed a screenful of warping texture. Then, without warning, I burst through and found myself falling once again, into a world both different and the same. Part of Yedoma Globula’s thrill is that it’s unfinished. Devoid of objectives, NPCs or utilities beyond a handful of airship jetties and some horrifying devices that call themselves teleporters, it’s a testament to how engrossing virtual landscapes can be when you resist the urge to fill them with routes and handholds. It’s a universe of chance gaps and unfriendly surfaces - porous floors that drop you into caverns so large there is no hope of return. But what makes it truly eerie is that it consists of 3D fractals. To hurriedly abbreviate some pretty hardcore maths, fractals are shapes that repeat themselves at larger or smaller scales. They were discovered (or at least, named) by the French-American polymath Benoit Mandelbrot, whose reputation-making tome The Fractal Geometry of Nature is a surprisingly readable blend of table-top RPG manual and mad science soliloquy. Mandelbrot didn’t come up with many of the equations that define fractals, but he was the first to visualise them using computers. Among the most famous fractal is his Mandelbrot set, an equation the length of an index card that produces an endless plunge through spiky rainbow archways, limited only by the hardware doing the rendering. Another famous fractal is the Sierpiński triangle, Link’s hunt for the Tri-Force played out at an ever-diminishing scale. These structures, indissociable from the rise of computer graphics, are mesmerising aesthetic objects. But fractals aren’t just ephemeral trinkets: they occur in everyday reality as well. Coastlines, for example, look similar whether you’re gazing from orbit or inspecting the beach between your toes. Pineapples grow according to fractal principles. The human lung branches like a tree, repeating itself at smaller and smaller magnifications. In Yedoma Globula, the repeated shapes are orbs, some planetary in scale, others tiny beyond sight. Often the results are beautiful, thanks not least to an eldritch play of lighting conditions I’m still trying to decipher. (There is apparently a day-night cycle - I have yet to locate the sun.) Sometimes, the surfaces call to mind intricate lacework, or snowflakes - another example of fractals in the wild. Other times, it’s like staring through a kaleidoscope into the eyes of a spider. The textures in themselves are worryingly organic, like flesh smoothed and polished into marble. But the idea that this is all one shape on endless repeat is a far more dreadful prospect than any passing resemblance to the art of H.R. Giger. In Mandelbrot’s view, the entire universe may amount to grander or smaller iterations of the same, played out indefinitely. Where does that leave you and I, creatures whose ability to comprehend the world seems to require distinctions and a degree of finitude - each individual thing taken this far and no further? It was with such questions in mind that I began an afternoon-length excavation of Yedoma Globula’s underside. I was hell-bent on uncovering either a hard barrier or a part of the world not comprised of self-replicating spheres. (I haven’t asked Bananaft to talk me through the game’s innards – he’s already written an essay about programming a fractal engine, which I understand approximately one tenth of, and besides, that would be spoiling the fun.) Like Samus Aran wielding a noclip cannon, I crept between the rinds of nested spheres, using flares not just for illumination but to work out which direction was down. I bounced through catacombs of overlapping interiors, and stumbled along bridges of pearls. I broke the skin of the world again and again. I also tested the limits of the game’s tools. The grenade launcher can only be fired a certain number of times in swift succession, seemingly determined by how much of a mess you’ve made with it. Disrespect this cooldown and you’ll trigger a klaxon suggestive of a hand trapped in a printer. Sometimes, if I fired too late while burrowing, the space squelched shut on me completely and spat me out into the nearest open chamber. How much of this misbehaviour had Bananaft anticipated when designing the tools? I dug and dug in a frenzy, fearful of causing a crash. I developed a particular appreciation for the game’s scanners. One of them, I belatedly realised, is an X-ray mapper, piercing walls and floors to reveal navigable surfaces beyond. With this latter discovery, I became more scientific in my descent, tunnelling toward the bigger, hollow spheres where I could let good old gravity take over. Over time, I gleaned a little of the artistic intent alternately guiding and meddling with the procedural generation. Yedoma Globula is far from a work of sheer abstraction: there’s a curated air to the central “biomes”, where lightpoles lead you toward apertures, and a sense of hidden, even sinister consequence to the tools. Take the teleporters, which are the only structures marked on your map screen. I’m still trying to work out what they’re for, but suffice to say they don’t always teleport you. The one on your airship is safe enough, whisking you back to the starting area, a small outpost of reassuringly non-fractal metal ramps and pipes. The ones you find further afield are… messier. Press the button and you’re exactly where you were, but everything else has been eviscerated. The walls and floors are gone. The labyrinth has become a glowering skybox held together by queasy rags of suddenly animate orbs, bubbling up and crawling over one another like ants. One of the other scanners provides a window into this neighbouring, nightmare reality during regular exploration. It’s not clear why you’d want to go there, but it’s easy, thankfully, to return. Just press the teleport button again and the world re-viscerates itself with a disgusting crackle. And then there’s the name. “Globula” means globe-shaped. “Yedoma” is apparently a kind of permafrost dating back to the Pleistocene, the thawing of which is a major source of atmospheric methane. There are shots of permafrost landscapes in Chukotka on Bananaft’s Twitter feed. I don’t know what this bodes, but it suggests that the game is about more than numbers talking to themselves. I also don’t know why some of the spheres emit noise: a gentle, cushioning roar, like the engine of a passenger plane. It’s to be hoped that later versions of the game - Bananaft’s plans include multiplayer, fauna and bigger airships - leave some of these mysteries intact. The last thing I want this terrifying, neurotic cave system to be is fully explicable. The developer’s efforts to organise it into a game already feel like an intrusion, crude edifices and implements shoved into a realm that doesn’t really exist for human consumption. I could definitely do with a universal save function, though. After four hours of heroic tunnelling I had to break off my descent to make tea, whereupon I discovered that I had no means of preserving progress. How would I mark this colossal enterprise? I mooched around a bit, then, in a fit of hubris, stencilled my name on a cave floor using the game’s rudimentary base-builder (right now, all it’s good for is metal platforms). Put that in your pipe and smoke it, Tenzing Norgay. The end? Not quite. It occurred to me that while I’d spent plenty of time drilling down, I had yet to do much horizontal pioneering. Starting a fresh save and jumping aboard my airship, I plotted a route between the larger spheres and outward into the seeping expanse of the skybox. Everything solid slowly vanished behind me. I could see nothing ahead save nebula-like formations that seemed, at times, like distant cavern walls. Would I reach a final, all-encompassing sphere, like the realm of the divine in medieval cosmologies, or just chug along until my laptop battery gave out? I held a steady course for about 10 minutes, pausing now and then to ponder the lonely green triangle surfing the blackness of the map screen. My finger began to ache from holding down the W key. Perhaps all there was to see out here was sky. But even skyboxes are finite, right - why else would they call them boxes? And what of the terrain beneath? Flexing my cramped hand, I peered over the side to launch some flares and fell out of my airship once again. For 10 minutes I tumbled - utterly motionless against the cosmos, my velocity given away only by the plunging line on the map screen. I pointed my scanners in all directions and saw nothing. 15 minutes of freefall. I fired my jetpack a few times to alleviate the boredom. 20 minutes. The sky darkened. I got up from the computer, made myself a coffee and started writing this article. Suddenly I heard it again, that faint roar of a passenger jet engine. I jumped up from the table and went back to the computer. I looked around but everything appeared the same. Then I opened my parallel world visor and saw something miraculous - a shaft of gauzy, orange light, like a planet’s ring when seen through its edge, petering away to nothing at its base. I waited for another 10 minutes, monitoring this bizarre, and as far as I could tell, non-spherical phenomenon, chucking energy grenades at it, trying to jetpack over to it. No further developments. I’m still falling.