And not just any old pet monkey, this is a pet monkey with the capacity to alter the course of history at any given moment, its idiot monkey paws tipping the balance of power one way or the other, determining the fate of epochs and chaperoning the fortunes of generations. When Old World is not being a typical 4X game – in which you build out your cities, develop tiles into resource-producing farms and quarries, and send scouts out to explore the map, scraping away the fog of war like fingernails on a continent-sized scratchcard – it plays more like an interactive novel. You’re living the private life of a ruler, as much as you are doing the actual business of ruling.

Decision points come thick and fast, but the pet monkey is a real wildcard. I’ve no clue what the chances of him appearing are, but if you choose to adopt him from a travelling salesman he might later show up during trade negotiations with visiting dignitaries, snatching a priceless totem from the bejewelled headdress of a high priest and scampering off with it. This sours relations for years to come, but nets you a rather heavy piece of jewellery for your palace coffers. On one occasion the monkey escaped into the streets of my capital city and caused so much havoc that I somehow lost an entire lumber mill. At each of these junctures I could either vehemently defend my monkey’s unruly behaviour, chalking it up to his peculiar brand of simian ingenuity, or give him the boot. I never could bring myself to fire him, and so each passing year became another throw of the dice. What would the monkey do next? What might he be capable of? It’s exactly the kind of mythical, colourful detail that brings actual history to life, this idea that powerful rulers were ever beholden to rude little monkeys or petty grudges with uncles. Old World delights in the roleplay of rulership, the conversations and meetings you imagine having with your AI opponents in Civilization are depicted here in rich, funny and sharply written dialogue.

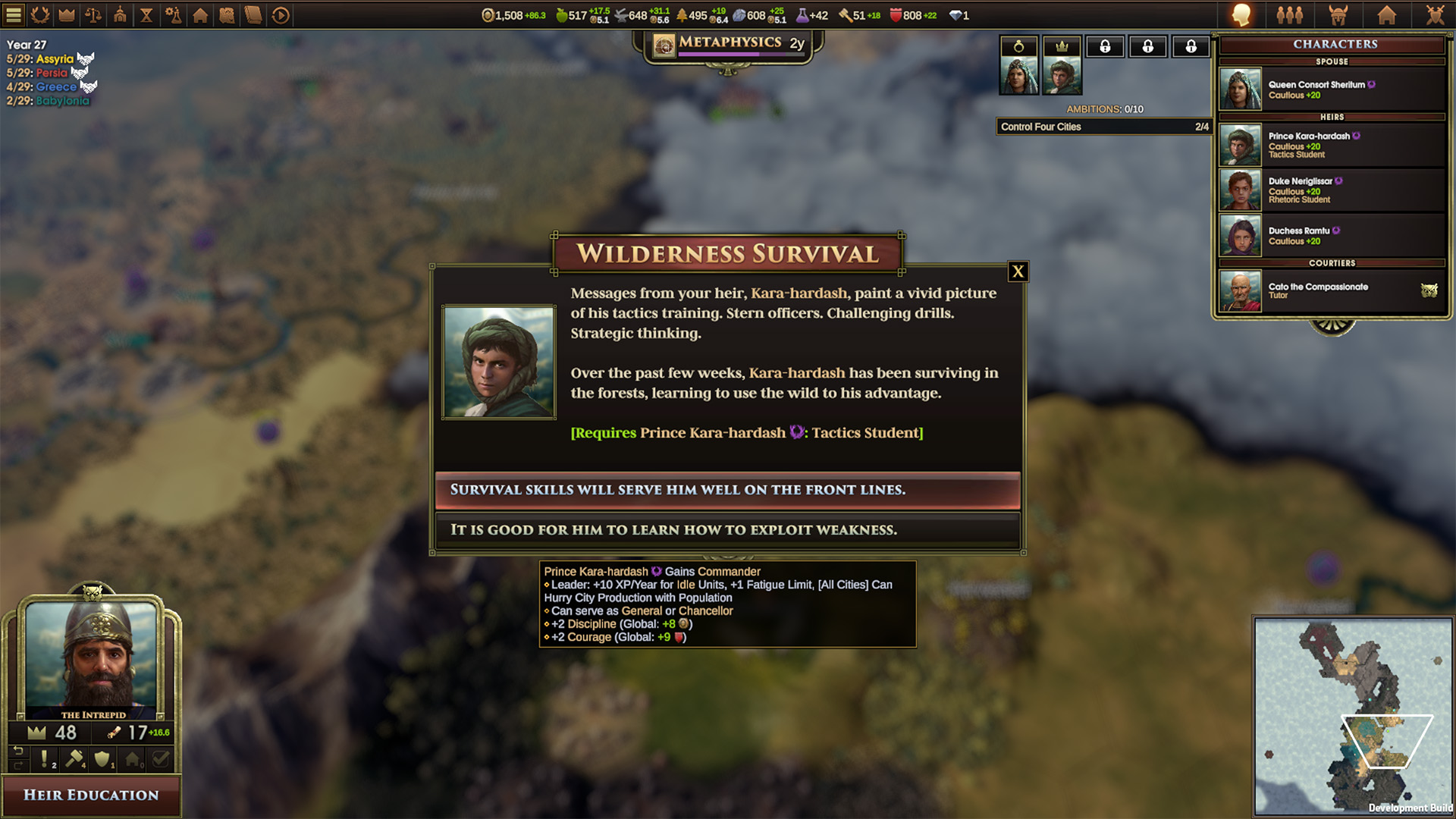

These events aren’t completely random, but driven by the specific circumstances of your game. What could have felt like forced, sporadic storymaking instead feels sensibly applied. This isn’t like pulling a chance card to win a beauty pageant in Monopoly, instead Old World tracks your relations with dozens of foreign leaders, family members, generals and courtiers, the contents of your tiles, your stockpiles and the state of the map, before presenting you with scripted events tailored to your situation. At a banquet with my firm ally Queen Xanthippe, for example, her young heir Prince Attalus boasted that he would make a better leader, and I was pressed to take sides. Attalus – who looks like he was fired from season two of the The Apprentice for failing the challenge where they have to make and sell a new kind of sorbet – was a liability, but old Xanthippe was getting on in years and it wouldn’t be long before her idiot son ascended to the throne. So I joined in on the mum-dunking, figuring I could easily manage the fading queen’s anger until she expired. Old World is at its very best when its leaders are approaching the grave, articulating through these dynamic events the machinations of treacherous heirs and decaying loyalties.

When you die, you embody your successor. If this is your son or daughter, the decisions you made as their parent are returned to you. Had my Babylonian king father sent me away to study rhetoric, and not sent me so much wine while I was in college, I would have had the required eloquence to appease both Queen Xanthippe and her son with some distracting wordplay. Small, seemingly inconsequential decisions shape future chapters of your empire’s expansion. It’s your basic chaos theory. A monkey doing a funny little dance in Babylon can cause Judaism to flourish in Athens. Back in the strategy part of the game, almost everything is determined by an overwhelming array of countable resources. Food, wood, stone and iron are all here, but so too are less tangible assets like civics, legitimacy and orders. Unlike the leading brand, each unit in Old World doesn’t get its own dedicated turn. Instead you’ve got a shared stockpile of orders to dispense, allowing you to focus efforts where they’re needed or pocket leftover orders to be used in other areas, such as promoting units.

This means that during peacetime you can effectively lend your military’s turns to your workers and scouts, developing your cities and exploring the world. When the fighting starts you can funnel orders into your armies to send them pinging across continents at lightspeed. Combat is one of the least developed parts of the game. Far from the extravagant detail lavished upon the tiniest aspects of diplomacy – whole paragraphs dedicated to the antics of the court monkey – battles are your run of the mill fish-slapping fights between two adjacent tiles. The growing and shrinking pile of orders makes each turn feel strangely elastic, and the movements of enemy units unpredictable. It takes a bit of getting used to, but by treating orders as a collectible resource like any other, Old World neatly plugs its top-level strategy game into its detailed empire management simulation. The rate at which you produce new orders is broadly tied to your legitimacy as a leader, and becomes a direct measure of your ability to effectively rule.

The deeper you wade into Old World the less like Civilization it becomes, until soon it’s only really the hexagons and the race to build a Parthenon tying them together. It’s a story engine as much as it’s a strategy game, one that revels in the playful details of the past, and represents history’s ancient rulers not as the pompous set of weirdos we’re all familiar with, but as capricious drunks, disastrous idiots and beautiful freaks with monkey butlers.