The remaster doesn’t exactly add to Inaba’s appeal, as Katharine has already written. This is one of those ports where the resolution hike strips the original assets of charm, roughening the edges of the cardboard grass and exposing the gaps between tiles on the map screen (the gorgeous anime portraits in dialogue come off rather better). The bareness of the porting suits the setting’s naffness, however – it’s appropriate that these environments feel out of date, like they’ve had the dust blown off them by an unscrupulous vendor. Inaba isn’t the kind of place you go for spectacle, though it’s a good backdrop for a funeral. It’s the kind of place where everybody seems a little stuck, from the lady in white you’ll encounter hovering by the town shrine at night, to the bug-collecting kid who can’t get enough of a particular soft drink. It’s the kind of place you leave behind. And yet here you are at the train station, bag in hand - a transfer student from the big city, wintering with your detective uncle Dojima while your parents are overseas. It’s not long after you arrive that the murders start. There’s another, more exciting side to Inaba, it turns out - a hazy otherworld that is accessed by clambering through a TV screen at the mall. Here, the unvoiced thoughts of the townspeople assume an exaggerated, tangible form, combining Jungian psychology with Japanese folklore and some whimsical modern touches. You can expect six-armed giants on rocking horses, and cops with golden keys where their hearts should be. Topical!

Somebody has been throwing people into the TV world, trapping the victim in a labyrinth of fear and desire with a monstrous Shadow personification of everything about themselves they cannot stand. The Shadow self - of whom you’ll catch glimpses on a supernatural TV station, the Midnight Channel - will eventually kill its counterpart, but only on a foggy day after several days of rain. Beyond the lengthy prologue, your job is to venture through the TV, battle to each procedurally generated labyrinth’s top floor and defeat the Shadow before the fog sets in, allowing the victim to embrace this buried element of their personality and join your team. This premise lends Persona 4 a simple but effective cadence, a back-and-forth between grubby normality and a garish realm of symbols and archetypes, drenched in CRT fuzz. You’ll find a different kind of game on each side of the divide. On the one hand, a snappy turn-based battler distinguished by a customisation system in which you equip and level up “Persona” spirits that endow the hero with different traits and abilities. On the other, a mix of visual novel and lifestyle sim, the mood set by a J-pop score that is as catchy and aimless as supermarket muzak. Besides gathering clues on the elusive villain, you’ll take allies on dates, study for exams, sneak out at night, sign up for part-time jobs, join the theatre, play sports, cook, fish and garden. These activities enhance social stats that unlock other activities, such as better-paying jobs, but more importantly, they strengthen your arm in the TV world.

The game’s halves don’t float apart, like town and dungeon environments in many RPGs. They colour and distort each other, for good and for ill. Every Persona you collect in the TV world and every major character you encounter is linked to a Tarot trump card. Bonding with people and helping them deal with various predicaments increases that character’s S-link rank, which unlocks skills for them while enhancing any Personas you conjure of the same tarot card. The conjuring itself is done in the Velvet Room, a Lynchian space-limo occupied by a wild-eyed fogey and his eldritch assistants. Here, you can register minions for later summoning (you can only have so many in your hand at once), and smoosh unwanted Personas together to fashion potent custom ability sets. The door to the Velvet Room is found on Inaba’s main street, a splash of blazing blue against the concrete. Time management is the key to Persona 4’s 70 hour+ story, with a range of endings dangling in the balance. Days are divided into morning, afternoon and evening, and most activities advance the clock, the crucial exceptions being shopping and fine-tuning your Personas. It gives rise to some entertaining indecision. Should you while away your Sunday with a book on studying methods, doubling the bump to your hero’s Knowledge stat when you hit the library? There are midterm exams in the offing, and everybody will like you more if you earn top grades. Then again, you’ve been ignoring your friend Chie and thereby, the absolutely brutal Personas associated with the Chariot card. Perhaps you should go out for lunch with her, and save homework till the evening. Or perhaps you’d rather dive into TV Land and sponge up some XP. The choice isn’t always yours: there are unavoidable calendar events such as camping trips, and characters pop up in different places at different times. Often, you won’t know whether you’ve made the best call till a few days after.

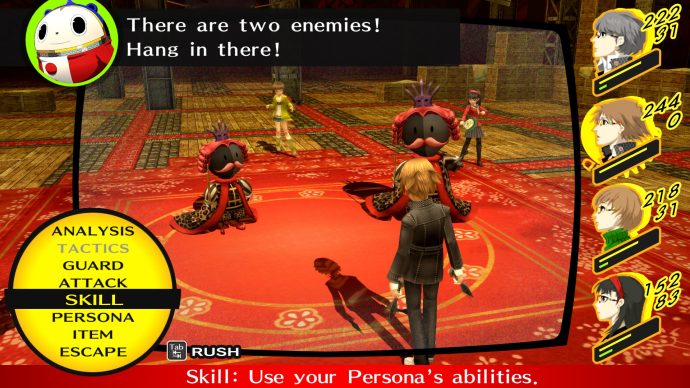

There’s a lot more predictability to the battles, which hinge on targeting elemental weakness so as to knock enemies flat, robbing them of their turn and earning your character a bonus move. Bowl every opponent down, and you can have your whole party pile on simultaneously in a billowing cloud of onomatopoeia. While the hero can switch Personas freely, party members only wield a single Persona, which evolves and shapeshifts as the story trundles on. These Personas correspond loosely to RPG classes like mage and cleric, which gives you some solid ground to fall back on while experimenting with different ability sets as the lead. There’s a lot of whimsy to Persona 4’s brawling, for all the quiet malice of touches like attacks that expend health rather than stamina. Battles often conclude with a nifty minigame where you pick from Persona, item and bonus cards in a limited number of moves. The game is also pretty considerate of your time, for all the emphasis on grinding between the major plot beats. Enemies are visible in the field and can be avoided. If you need the XP but you’re weary of the fray, you can turn on party member AI and hit “Rush” to fast-forward each battle. As a secret dimension generated from a broadcast medium, the TV world allows Persona 4 to explore how our innermost selves are shaped by the expectations and projections of others. It digs into the worrying thought that even our deepest drives are always, in some way, public property. One of your companions is a pop idol who fears that her identity is being devoured by the sexualised infant she’s obliged to play on-screen; her Shadow is a rippling pole-dancer with a satellite dish for a face. Subtle these renditions ain’t, and there’s a decided sleaziness to the game’s “critique” of feminine stereotypes, but the writing is witty and sympathetic enough in the moment to keep you nodding along.

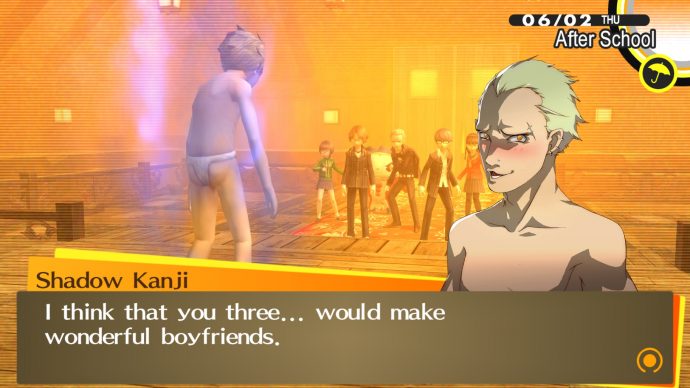

At least, that is, before you run into Persona 4’s extremely dubious, are-they-or-aren’t-they renditions of gay and transgender people. Beware of major spoilers from this point on. Another of your companions is Kanji, a macho outcast in punk leathers. His TV world dungeon is an erotic bathhouse, and his Shadow self is a cavorting, blushing figure in a loincloth. The very obvious suggestion is that Kanji is gay and struggling to deal with this, but later, he tells you that he identifies as heterosexual - his deepest fear is actually of rejection because he enjoys feminine-coded pursuits like sewing. There’s a lot of discussion of this scene, with some arguing that the game’s representation of gayness is beside the point – Kanji’s tale is purely about gender expectations. For me, it’s a bait-and-switch that allows the game to avoid reckoning with the implications of the bathhouse dungeon, where being queer is flamboyantly associated with “unmanly weakness”. There’s a definite homophobic undertow to Persona 4’s writing. Dialogue with Kanji often goes beyond recreating the prejudices of teenagers into treating bigotry as a source of comedy. At one point, the game’s class clown Yosuke asks Kanji whether he and the hero are “safe alone with you”, clearly evoking the stereotype of the gay man as a predator. The portrayal of Naoto, a youthful genius detective who wears male-coded attire and accepts male pronouns, is equally questionable. Naoto’s appearance and manner are eventually positioned as an attempt to fit into a profession where women are belittled: it’s a strategic gesture, in other words, not a statement of identity. But Persona 4 is hazy on this distinction, often representing Naoto as deeply uncomfortable with being perceived as female, which makes framing him as a woman navigating a man’s world feel akin to gaslighting.

As Carol Wright has written, the character’s TV world dungeon - a military base housing a patchwork Naoto puppet - is a thin allegory for the act of persuading somebody not to undergo gender reassignment surgery. Later, in the course of completing his S-Link story arc, you’re able to congratulate Naoto on being “born a girl” and even correct the pitch of his voice to sound more feminine, after which he’ll come to an event in a schoolgirl uniform rather than his usual attire. It feels like you’re playing out the convictions of social conservatives who would rather tell trans kids they’re “confused” than love and support them. For more on this front I recommend Vrai Kaiser’s lengthy article from 2015, which also digs into how Kanji and Naoto reflect perceptions of queer and trans people in Japanese society. These failings are depressing because Persona is rare among blockbuster videogame series for giving space to queer and trans characters, and the developers are often quite deft at telling stories about adolescents navigating a broken society that preys upon their youth and naivete. Even Kanji and Naoto are well-rounded, sympathetic personalities, if you close your eyes to what they suggest about the prejudices of their creators. That likeableness only makes the nastier elements of their framing more insidious. Persona 4 is a twisting tale of dreams gone rogue in a town sapped of purpose. It brings personal demons to life in gaudy but plausible ways, and uses this to rejuvenate the dog-eared framework of a town-and-dungeon fantasy RPG. Unceremonious as it is, the PC port leaves all of that peculiar magic intact. It’s just a shame that the insight and empathy on show here doesn’t extend to everybody.