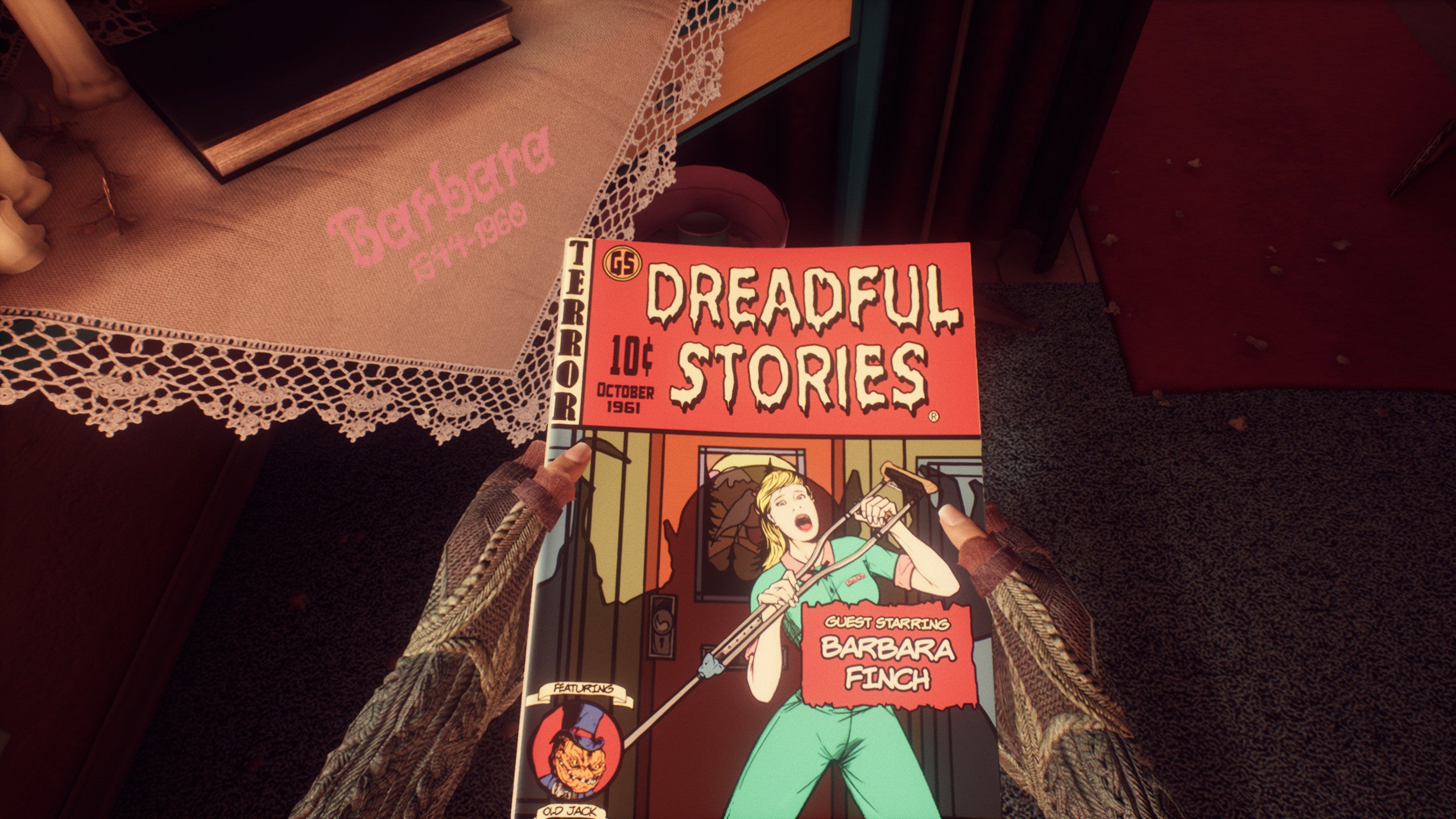

Edith Finch is returning to her family home years after they suddenly abandoned it one night. It is a stunning home, with rooms added over years until it rises wonkily into the sky. When a member of the Finch family dies, see, their bedroom is preserved as a shrine, each generation requiring a new extension. What a house! What Remains is building on the bones of games like Gone Home, a first-person explore-o-story set around a single home. While the story is grim, the setting pushes hard into whimsical for contrast. Like the setting of a Wes Anderson movie about hoarders, it’s an explosion of colour, decoration, and clutter, each room manifesting the resident’s interests and personality. A great game for fans of staring at stuff. Walk-o-stories grew from immersive sims and here I do feel more Thief and Deus Ex influences than many in the genre, with Edith getting around the house by uncovering secret passages, clambering over rooftops, and so on. And the obligatory audiologs and diaries are expanded into something stunning. When Edith reads a family member’s diary (or looks through their photos, or other strange and wonderful documents), we see their final moments come to life in interactive vignettes. It is tragic to play through people’s deaths, though they’re often beautiful. These sections dance across many presentation styles and video game genres, making each death a moment of discovery and joy. They can poetically reflect a person’s life too, celebrating them at their end. I want so much to talk about some but it’s best you see for yourself. The game’s two or three hours long, so hop to. For folks who (like me) already played What Remains Of Edith Finch, hey, you might enjoy revisiting it too. It holds up, and I am surprised to realise it might have quietly become my favourite explore-o-story. The house is still a wonder, and how great/awful to enter with full knowledge, realising quite how many traces of tragedies are scattered around. And the dreamy deaths are still both astonishing and affecting. It is curious to vibe with the game’s mood more on a second playthrough. I’ve now five fewer years left in my own life and, more significantly, I suffered two gutting bereavements last year. My father died and, soon after, a beloved uncle. My grief is still raw, my sorrow now so close to the surface, and as I replay it this week I often need to stop for a little cry. I don’t think games about death and grief are inherently profound, nor do I think it’s a staggering artistic accomplishment to make make people cry. Mate, I’ll cry at anything where an orchestral score rises as someone commits a redemptive act of self-sacrifice. I’d cry if you put googly eyes on a slice of buttered toast and filmed it sliding off a plate in slow motion. But I like what Edith Finch is doing with its many deaths (even that particular one I know some players felt was a brazen cynical attempt to shock). I like the many layers of stories in the game. We have the whole framing story, the handed-down stories Edith retells, the stories the people write about their own lives and deaths in their diaries, the dreamy versions of those stories we play through Edith’s eyes, and the stories we create as players combining those fragments with what we see in the house. None of these stories are complete and some are barely real, but they’re all true in a way and they all matter—even if they can be dangerous. The lives of the Finch family revolved around death. They built their deaths into not only a story which doubtless ended at least one life, but also into an increasingly hapzard and unsustainable home. Each day, the living would need to scale the many stairs to find their own lives, sleeping teetering above shrines. Edith’s grandmother believed in memorialising, preserving bedrooms as if the person had just left, with the addition of a shrine formed from keepsakes to tell crystalise a snapshot of who she thought they were. She more actively shaped certain stories rather than confront them, too. Edith’s mother later sealed the rooms with locks and foam as she attempted to protect her children from it all, until they fled. Now here’s Edith come home to learn the stories and secrets and maybe pull them together. Stories have prospered after dad’s death. I’ve heard new stories from across his life, and found more by looking through his keepsakes. Some family secrets and shames have been entrusted to my generation so we might better understand. I’ve learned secret secrets too, ones locked in hearts until this kick of finality made people realise they could miss the opportunity to share. Many friends and family have told me stories of who he was and what his life was and why and what it all meant. No two match. Like all people, my dad was a knot of contrasts and contradictions. He was perhaps spikier than some. He was often my hero, and I was often terrified of him. I think my siblings and I had each hoped we would one day experience some moment of openness and mutual understanding with him, that we might pull the loose plot threads of our relationships into coherent stories. Then he was in a hospice bed, unable to speak and eventually, probably, unable to listen. But my sister and I told him a story over and over as we sat there day after day: you’ve been strong for us for so long, and you’ve made us strong, so it’s our turn to be strong for you, and you can go now. God, I wish that had worked like it does in the movies. My favourite discovery in dad’s effects was a letter of reprimand from soon after starting the job which became his career. In it, his boss detailed the many responsibilities dad had shown no interest in. From writing reports to dealing with clients, it reads like a job description with “You don’t care about…” stuck on the start. He never grew to care about the job but he learned to fake it. And he kept that letter. I like to think he was proud of the scolding, rebellious young punk that he once was. When we finally settle his possessions, I’m getting that letter framed alongside a photo we found of him looking bored out his skull on the train to work. I know this is me binding events together but I’m okay with it on this scale, as long as I remember it’s a story I wrote. I couldn’t tell one all-encompassing story of My Dad’s Life. I don’t want to. All the stories are true in a way, the good and the bad, and especially the unlikely and the contradictory. When all that remains of my dad is stories, to discard any would be to lose him even more.