(Click here for Part I)

The Ventnor currently unfurling beneath us is a very different resort to the one described in Roman’s antique guidebook. Deprived of its remaining* railway station in 1966, its imposing sanatorium in 1964, and the last remnants of its pier in 1993, it has - reluctantly perhaps - regained some of the sleepy insignificance it possessed in the days before the Victorian tourists and TB sufferers arrived in their thousands.

- There are few better illustrations of Railway Mania folly than Ventnor. Working independently, two railway companies burrowed through the massive chalk bulwark of St. Boniface Down to reach the town.

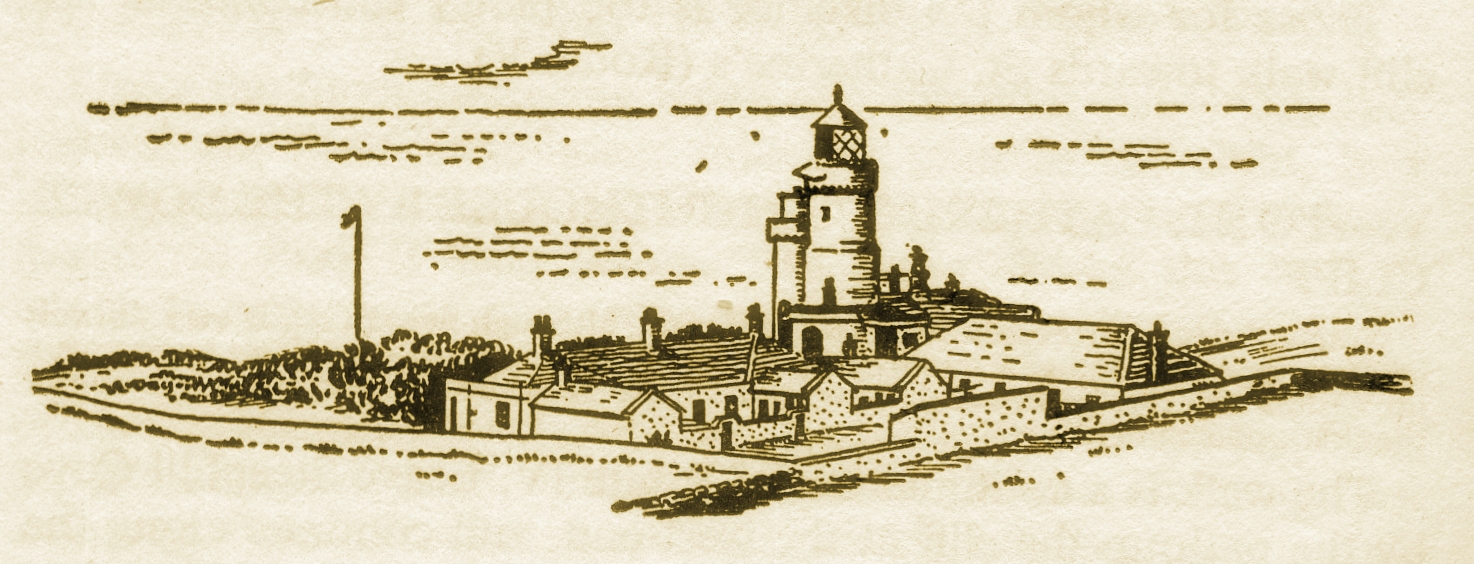

Beyond Puckaster Cove, a smuggler-friendly scrap of sand where a storm-spooked Charles II once came ashore, is St Catherine’s Point. The Point’s whitewashed navigation aid is proof that lighthouses can be built too tall. Constructed in 1838, St Catherine’s was shortened by thirteen metres in 1875 to bring its lantern room below the level of the mist that frequently shrouds the hilltops in these parts.

The site of three WW2 deaths (keepers killed in 1943 when the engine house they were using as a shelter was struck by a Luftwaffe bomb), the lighthouse was the blind witness to a tragedy of far greater magnitude on the morning of February 21, 1917. That was the fateful day SS Mendi, a troopship making for Le Havre with 823 men of the South African Native Labour Corps aboard, sank in thick fog ten miles south of the Point after being run down by the Darro, a recklessly captained freighter. The Darro failed to stop, and despite the best efforts of HMS Brisk, the Mendi’s escort, 646 people drowned. The words spoken by Isaac Williams Wauchope to the men who crowded the deck of the doomed vessel after the collision, have entered South African folklore: “Be quiet and calm, my countrymen. What is happening now is what you came to do…you are going to die… Brothers, we are drilling the death drill. I, a Xhosa, say you are my brothers…Swazis, Pondos, Basotho…so let us die like brothers. We are the sons of Africa. Raise your war-cries, brothers, for though they made us leave our assegais in the kraal, our voices are left with our bodies.”

St. Catherine’s isn’t the first beacon-topped tower to sentinel the Island’s southern-most cape. The stone rocketship a mile to the north, is Britain’s only surviving medieval pharos. A local lord built St. Catherine’s Oratory in 1328 to placate the Church, after he was discovered in possession of ecclesiastical property (wine) plundered from a local wreck. Today, the Pepperpot, as it’s affectionately known, looks down on the oldest amusement park in the UK. Named after a ravine long since obliterated by landslips, Blackgang Chine still boasts the crooked house, wild west street, and life-size fibreglass dinosaurs that dropped the jaws of juvenile visitors like me back in the 1970s.

Ahead stretches the Back of the Wight, a portion of the Island devoid of towns and shunned by 19th Century railway engineers. Although sparsely populated, the area has produced dozens of decorated heroes over the years. If these heroes had won their medals with the aid of pistols, rifles and machine guns, rather than oars, tillers, and ropes, then, today, tiny villages like Brook and Brighstone would be famous throughout the land as kindergartens of courage.

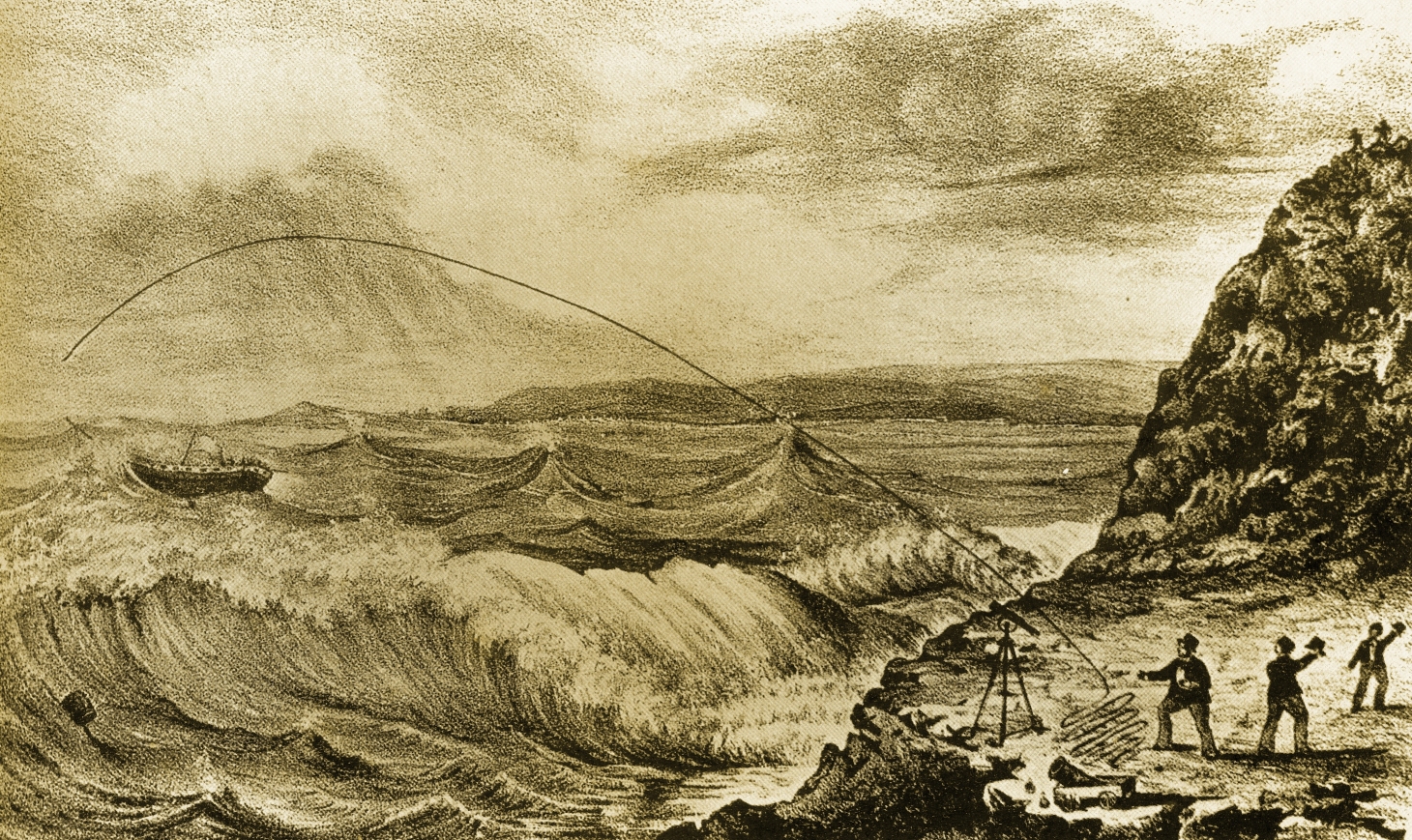

Not that all the rescues on this treacherous stretch of coast involved local lionhearts in open boats. On October 8, 1832, oilskinned villagers braving gale-force winds on that headland down there, plucked nineteen souls from a vessel lodged on the notorious Atherfield Ledge, with help from what was then unproven technology - a line-carrying rocket. The rocket in question was designed by John Dennett, an Isle of Wight man who had learnt his trade engineering life-taking rockets for the Army. Metal-cased, 2.5m in length and with a 230m range, Dennett’s fireworks went on to save thousands more lives before a more sophisticated design superseded them.

Two landmarks visible on our two o’clock right now are worthy of attention. That tree-hemmed mansion above Brook (a) was the home of Jack Seeley, a dashing cavalryman and high-flying politician. The depth of Seeley’s affection for Warrior, the horse that carried him, almost unscathed, through the Great War, can be judged by the fact that “the luckiest man in the army” penned a biography of his mount in the 1930s.

See where the road out of Brook adders through that cleft in the downs? The bald patch of chalk on the left (b) marks the spot where a Short Solent flying boat struck the hillside in 1957. ‘City of Sydney’ was on her way from Southampton Water to Madeira (which, at that time, lacked a runway) with 58 people aboard when one of her four Bristol Hercules engines packed up not long after take-off. She turned for home but, due to the unexplained stoppage of a second engine, only made it as far as that shoulder of downland. The accident claimed the lives of 45 and sounded the death knell for Aquila Airways and commercial flying boat operations in the UK.

Legislation designed to discourage a sequel to the music festival featured in the first part of this tour, wasn’t successful, but did mean the 1970 event went ahead at a site that was far from ideal. Held at East Afton Farm – passing on the right at present – the third IoW festival enticed a veritable multitude to the Isle with a stellar line-up that included Jimi Hendrix, The Doors, Miles Davis, Sly and the Family Stone, Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen, Joan Baez, Chicago and Jethro Tull. Many of the estimated 700,000 who attended were able to watch performances for free from the slopes of Afton Down. This, together with low ticket prices and trouble caused by French Maoists…

…scuppered prospects of a 1971 festival. It would be thirty-two years before the Island’s next music festival, and that revival, when it came, was comparatively small-scale and almost entirely free of angst, aggro, and acid.

Tarka raising his nose to ascend Tennyson Down is my cue to draw your attention to Farringford House, the residence of one of Britain’s best known and most quoted poets. If you’ve ever uttered “Tis better to have loved and lost / Than never to have loved at all”, “Their’s not to reason why / Theirs but to do and die”, or “Nature, red in tooth and claw” you’ve quoted Alfred, Lord Tennyson, a Victorian Poet Laureate who produced much of his best work while living at Freshwater. The prone-to-melancholy* wordsmith behind compositions such as The Charge of the Light Brigade, Crossing the Bar, and In Memorium of A.H. (a poem that “soothed and pleased” Queen Victoria after the death of Prince Albert) strolled daily on the down that now bears his name. According to him, the air up here was worth “sixpence a pint”.

- T. S. Eliot described him as “the saddest of all English poets”.

Prepare to gaze in disappointment at the Island’s famous calciferous coccyx!

Brutally flattened by GeoFS’s open-weave elevation mesh, the Needles extend a west-pointing promontory, that, in the 1950s and 60s, was at the centre of Britain’s ballistic missile and space programmes. The Black Arrow rocket that made possible Blighty’s one and only ‘single-handed’ satellite launch, relied on engines built at East Cowes (on our itinerary) and tested on the concrete pads at each end of that quarter-circular service road. To the relief of local fauna, the deafening tests ceased in 1971 when Whitehall cancelled Black Arrow on economic grounds.

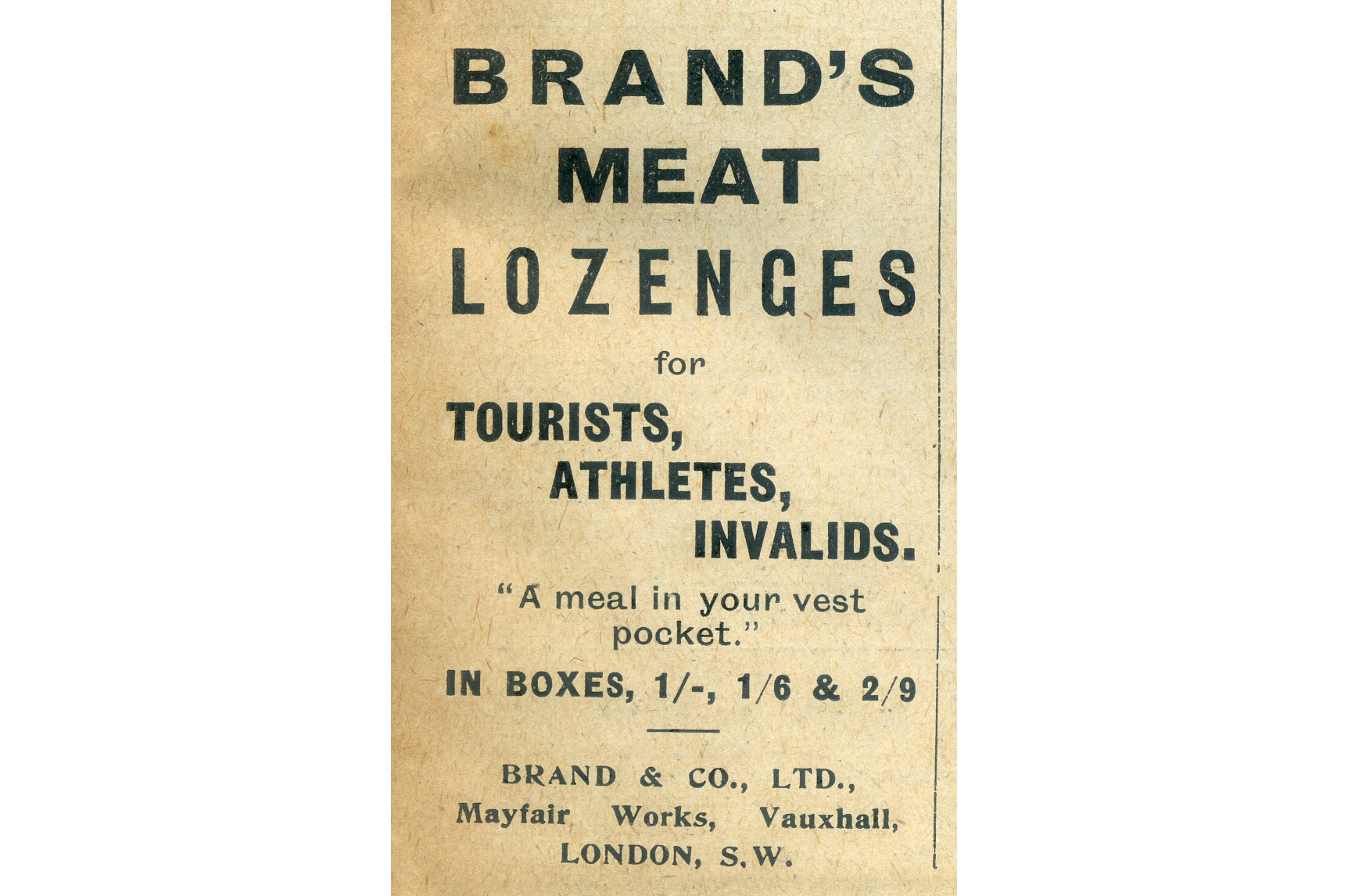

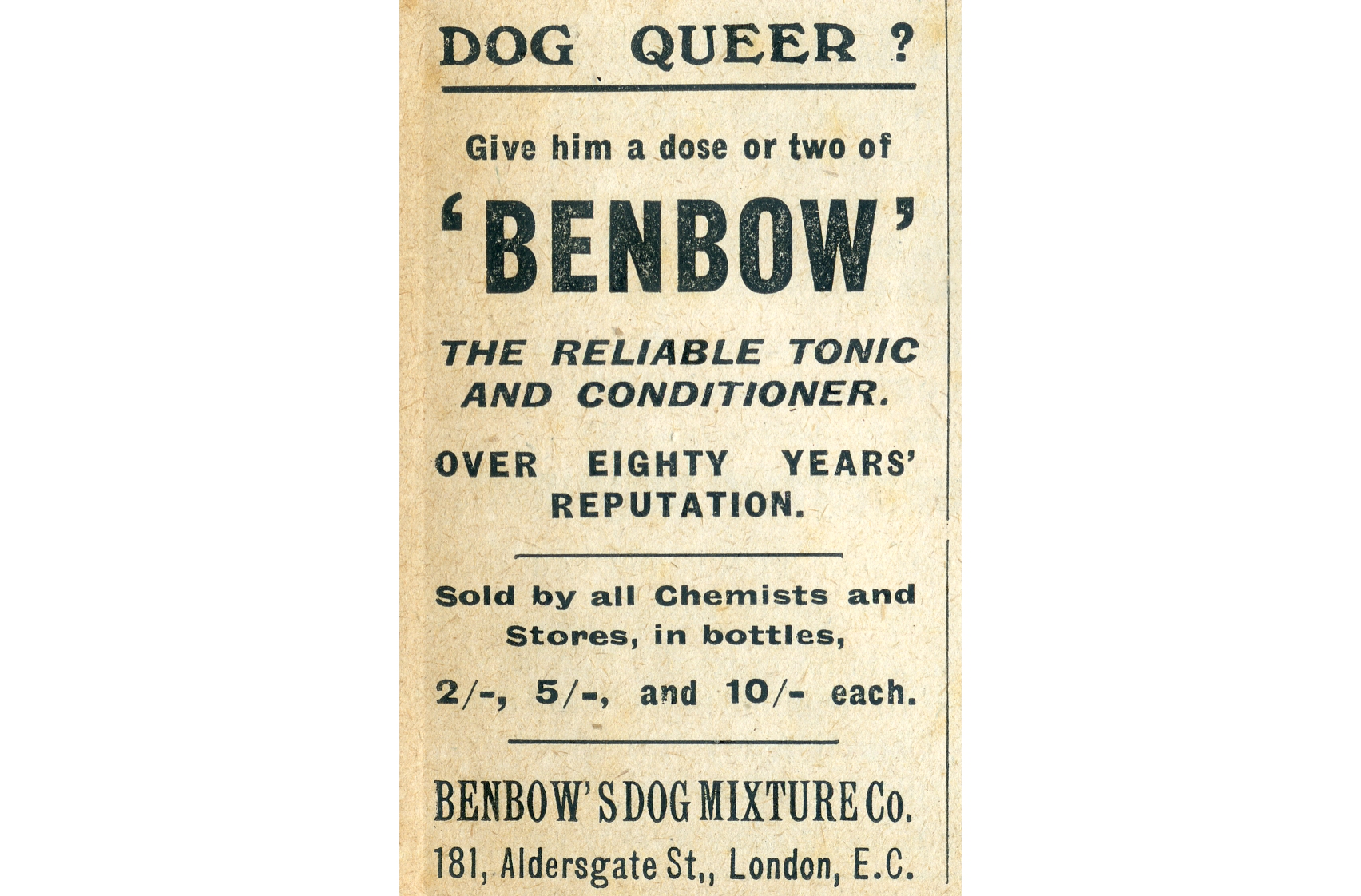

I see some of you haven’t touched your Dino Bones. Realising Marmite-coated wheat snacks might not be to everyone’s taste, we did bring an alternative. Advertised in Roman’s Edwardian guidebook and sourced with the help of a food historian pal of ours, the delicacies I’m about to hand round are guaranteed to keep hunger pangs at bay until we get back to the mainland.

Blimey, I don’t like the look of those fuel gauges. If we’re to avoid a repeat of that incident in 2017 when Flare Path Sky Tours passengers ended up uninvited guests on Geopotes 15, a Greek suction dredger moored off Malta, I think we’re going to have to loiter less from here-on. Onwards to Alum Bay, Roman..

Alum’s candy-striped cliffs read like a geology textbook’s index. Not only has Mother Nature surrounded the cove with an astounding range of sediment beds, the dear old thing has thoughtfully rotated said strata through ninety degrees to make inspection of them that bit easier. The 1916 Ward Lock believes the rainbow-hued ramparts, ruthlessly pillaged over the years by souvenir crafters and sand painters, are best seen from the deck of a steamer: “The tints of the cliffs are so bright and so varied that they have not the aspect of anything natural. Deep purplish, red, dusky blue, bright ochreous yellow, grey nearly approaching to white, and absolute black, succeed each other, as sharply defined as the stripes in silk."

Palmerston’s pale pachyderms (see part 1) dot the next four miles of coastline. Keep your eyes peeled for shrub-softened battery sites and repurposed casemates. Facing Hurst Castle, a much older strait sentry on the mainland, Fort Albert is one of the more interesting as its arsenal once included a steampunk guided missile. Any hostile surface vessel using the Solent’s western entrance during the final decade of the Nineteenth Century would have had to dodge wire-guided Brennan torpedoes launched and directed from Fort Albert.

Amazingly, the revolutionary weapon wasn’t just steered by steel cables, it was powered by them. The explosive eel contained no motor, only spools of wire. A shore-based engine propelled it by rapidly winding in the wire.

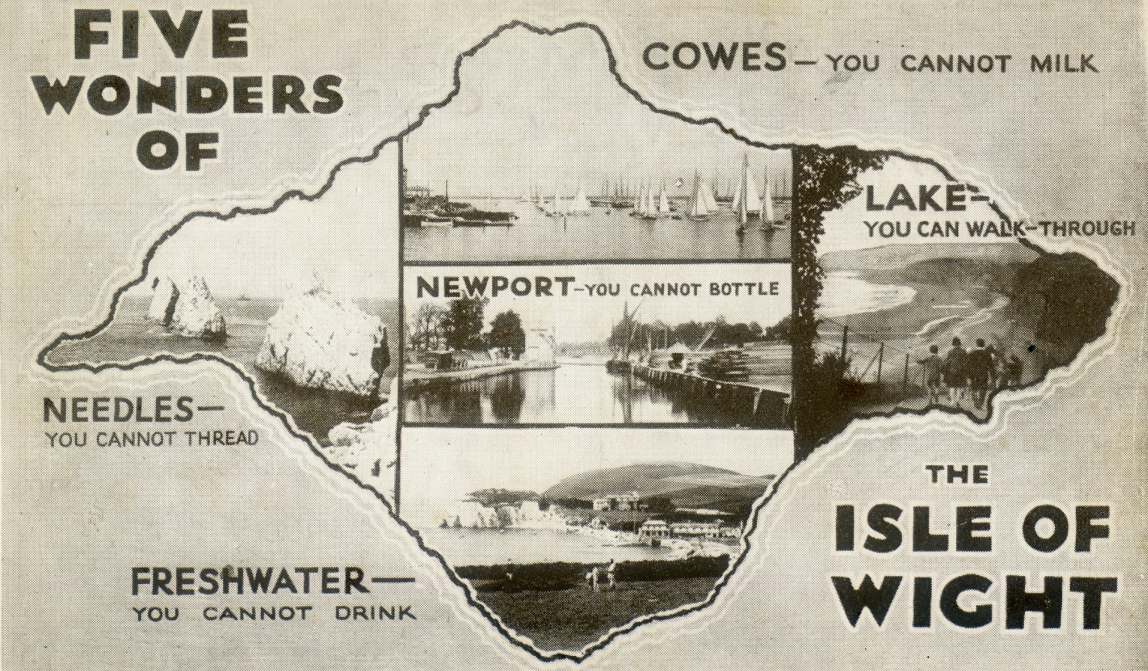

That’s Yarmouth dead ahead. Robert Holmes, an aggressive Royal Navy sea-dog who started the Second Anglo-Dutch War virtually on his tod, and secured a mention in Flare Path Sky Tours’ Dutch dawdle by torching West-Terschelling in 1666, resided in the town on the few days a year when he wasn’t busy bothering Netherlanders. He’s buried and memorialised at St. James’ Church, a stone’s throw from his old waterside home, now the George Hotel (x).

You could be forgiven for missing “probably Europe’s most important Mesolithic site” a few miles up the coast from Yarmouth. Hidden under brine close to shore fringed by Bouldnor Forest, it doesn’t exactly catch the eye. Archaeologists discovered “Britain’s Atlantis” with the help of an industrious lobster. The house-proud crustacean was in the process of removing worked flints from his burrow when spotted by divers. Subsequent excavations* revealed the unusually well-preserved remains of an 8000 year-old pre-Solent forest settlement and items such as tools, timbers, and string that have changed the way academics think about the Middle Stone Age.

- By humans not lobsters.

From Bouldnor we cut inland, following the serpentine course of a long-gone railway line, to a village which, in 1916, was hospitality embodied (“Every other house bears the legend ‘Teas provided’”). The reason for Carisbrooke’s incredibly high CSPC (cake stands per capita) was the motte-and-bailey fortress below us.

While it’s John Trenchard and Elzevir Block I tend to think of first when I hear the name Carisbrooke Castle, it would be churlish to deny that the place has had better known guests in its time. Charles I fled to the Island in 1646 after escaping house arrest at Hampton Court, but quickly realised he’d merely swapped one prison for another. Restricted to the confines of the castle after Parliament realised he was endeavouring to restart the Civil War with help from Scottish Presbyterians, he devised several escape plans all of which miscarried*. The price he paid for the failures was high. After a brief sojourn at Hurst Castle, the inveterate schemer was whisked up to London for a speedy trial and a bloody appointment with a headsman’s axe.

- Some comically. One bid had to be abandoned after Charles got wedged in a window frame. Roman, do you reckon we have sufficient avgas to take in another prison on the way to Cowes? Shame. I had a mind to tell the story of that 1995 breakout. The one where the escapees tried to pinch a Cessna from Sandown Airport.

Straight up the River Medina to Cowes it is then.

On the night of 4-5 May, 1942 the water of the river that cleaves the Island’s only port in two, was put to a use it had never been put to before. It was used to cool anti-aircraft gun barrels aglow from prolonged firing. The guns belonged to a Polish Navy destroyer that happened to be in Cowes undergoing a refit when the town sustained its worst air raid of the war – an attack by 160 bombers. The Błyskawica’s doughty defence of her birthplace (the ship was the product of local shipbuilder J. Samuel White) has never been forgotten by Cowesians. Francki Place in the heart of the town is named after the DD’s captain, and modern Polish warships pay regular visits to participate in commemorative events.

One of the reasons the Luftwaffe lavished so much H.E. on Cowes was the Saunders-Roe works that once hugged the shoreline next to the East Cowes ferry terminal. Known for its flying boats, the last of which was the gargantuan Princess (a type that never carried a paying passenger but was briefly considered as a candidate for conversion to nuclear power) the company was the natural midwife for Christopher Cockerell’s bizarre brinechild, the SR.N1. Recall those giant cross-Channel hovercraft we inspected at the start of our journey? Like the SR.N1, the three Princesses, and the world’s first flying-boat jet fighter, their womb was that Art Deco hangar by the concrete quay (x).

As Tarka’s fuel gauge needles are both nudging zero, and several of you seem to be in urgent need of toilet facilities (I was assured those lozenges were fit for consumption!) a swift return to Lee-on-Solent would seem sensible at this point.

The final kink in our flight path is over a landmark that’s only visible a few days a year. Roughly two miles north of Cowes, bramble-free Bramble Bank hosts an annual cricket match between two yacht clubs, and hit the headlines most recently in 2015 when it was used as a sandy crutch for listing roll-on/roll-off/roll-over car carrier MV Höegh Osaka.

Ladies and gentlemen, in preparation for landing, please fasten your seatbelt, turn off all electronic devices, stow your tray table, and put all thoughts of bird strikes, blown tires, carelessly parked fuel bowsers, and undiscovered WW2 runway explosives out of your mind.

Three out of ten, Roman. If GeoFS modelled chain-link fences, Tarka would be wearing one like a stole now.

This Flare Path Sky Tours flight ends here, a convenient twenty second sprint from the terminal’s public conveniences. Thank you very much for flying with us and apologies again for the meat lozenges.

* * *

This way to the foxer