Night turns to day in Fallout 76, the sun coaxing new fruit from the tato plants in my garden. There are even seasons of sorts, the West Virginian forest waxing and waning according to its own schedule. But, as in most RPGs, real change occurs only at the player’s convenience. Quests await activation, and the Scorched plague rolls on until I deign to find a cure, playing second fiddle to my ambitions of bringing interior design back to Appalachia. With the exception of the other players wandering the wastes, the world of Fallout 76 is static, moving only when I do. Until recently, that is. “It’s hard to leave a game up and then also pretend like it’s a year later without all this crazy heavy lifting,” project lead Jeff Gardiner tells me.

And what a year it’s been. When Fallout 76 launched, it held true to a bold design directive: the only human beings in its world would be players. “It was the big experiment,” Gardiner says. “We had to really wrap our heads around that, because we realised the difficulties we were going to have with storytelling and the other things that people had come to expect from a Fallout game. There were several times we balked and tried to walk it back.” “There were even people on the team that very much wanted to have human NPCs there at the beginning,” lead designer Ferret Baudoin says. “To say every decision was made with 100% confidence, no. This was something new.” Ultimately, though, this peculiar vision won out. Bethesda’s Fallout games have always had an archaeological bent, and in 76 that came to the fore, with stories told exclusively through old tapes, dusty terminals, yellowing notes, aged robots, and the careful placement of corpses. It rendered West Virginia an open-world Gone Home. But it proved a step too far for many fans and critics, who found Fallout 76’s world to be empty. Such was the explosive yield of its review bombing that the game is still considered radioactive: when it finally appeared on Steam in mid-April, users rushed in with thumbs down, embracing a new platform on which to release old frustrations.

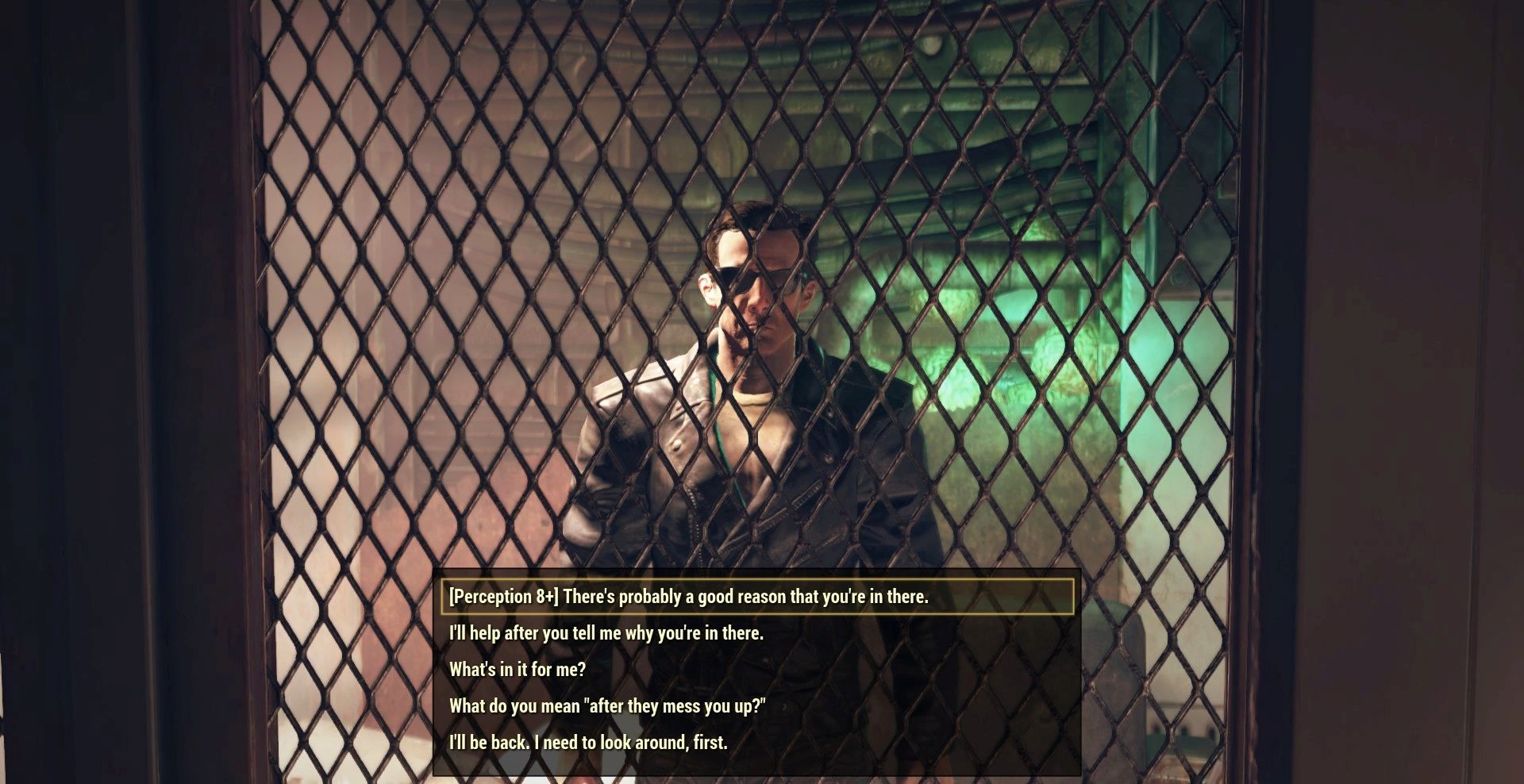

From the off, fans were adamant that the game needed human NPCs, and Bethesda was faced with the daunting prospect of reversing a core design principle. Gardiner, however, had been at the studio long enough to remember the last time that happened. “When we put out Fallout 3, the game ended,” he recalls. “You finished that main quest and the game was over. And we had a massive outcry over that.” A decade ago - years before Mass Effect 3’s ending was tweaked after release - Bethesda undid Fallout 3’s conclusion in DLC, refashioning a story of personal sacrifice to allow players to walk the ruins of Washington indefinitely. Today, that uproar is barely remembered, and Fallout 3 is regarded as a high point in the studio’s history. With that in mind, Baudoin sat down with Todd Howard to work out the story of Wastelanders. “In Bethesda games, it’s amazing how intricate the web is,” Baudoin says. “You pull on one strand, and soon the whole web is coming. It’s like, ‘Dude, I just pulled this one strand!’. This wasn’t a small strand, and so very predictably, it just spiralled out to everything.” Untangling Fallout 76’s narrative took a concerted effort, and the load was shared by developers thousands of miles apart. Seasoned Skyrim and Fallout 4 alumni at Bethesda Game Studios HQ in Rockville joined the Austin team to tackle the extraordinary number of words required to repopulate West Virginia with talking NPCs. Writers flagged up old lines that would throw off the game’s changed timeline, and set about rewriting them.

The problem of interweaving old quests with new is summed up neatly by Rose, the raider robot who, since launch, has occupied the tower of Fallout 76’s ski resort. Her entire motivation has been to bring the raiders back to Appalachia, and sure enough, here they are, showing up as one of the key factions in Wastelanders. Yet Rose can’t join them: from a practical perspective, she has to stay rooted in her original spot to dole out the same quests she always has. “The decision to incorporate Rose into the main quest of Wastelanders was us tackling that head on,” Baudoin says. “She’s already a very involved character in the original story, so we had to do that.” As it transpires, the same slacker mindset that led Rose to become a raider puts her off the idea of leading them now they’re back; besides, the white powder of the Toxic Valley, where the new crew has holed up, would be hell on her filters. Playing Wastelanders, you can feel the tonal shift that Fallout 76 has undergone. In the original game, the story threads you followed were uniformly melancholy. Since you couldn’t happen across any of the human characters they concerned, every hope had to be dashed - the former residents had all been killed, displaced or transformed into ghouls before you ever left the vault. “You’re right, it’s macabre,” Baudoin says. “Literally everyone died. There was no-one that made it. Every time somebody on the team would try to sneak in a survivor, I would catch it, and they would die.”

With the arrival of human NPCs, the vast graveyard of West Virginia suddenly has a future. There’s an air of optimism ingrained in the dialogue, which Baudoin says is a reflection not just of the plot, but of the way players have behaved over the past year and a half. Rather than treat Fallout 76 like DayZ, players flung open the doors of their ramshackle houses and embraced strangers. “They helped each other almost exclusively,” Baudoin says. “It was kind of nutty, just how friendly everyone was.” It might sound like PR guff meant to flatter the community, but I’ve seen it for myself. There is a prevailing kindness to online interaction in Fallout 76, as if scarcity of human contact made players grateful for one another. You might just understand it if, during lockdown, you’ve had an unusually enthusiastic conversation with a neighbour over the garden fence. “I tried to reflect that in the way that NPCs talk about the 76ers in Wastelanders,” Baudoin says. “They came out of the vault and they made Appalachia better. They made it liveable enough that we have people coming in.” Despite the deep flaws Fallout 76 had at launch, a dedicated playerbase had responded to its mournful tone, and the freedom it granted them to carve out a lonesome corner of its world. And even as Bethesda transformed the game with Wastelanders, it had a responsibility not to overwrite the experiences of those players.

“I definitely wanted to augment and not supplant what was there,” Baudoin says. “We went through a lot of effort not to retcon anything. All the stuff that happened, happened, and we respect that.” Even accounting for temporal dissonance, long seasons have passed since Wastelanders was announced. Its original release date was last autumn, but slipped twice. Partly that’s as a consequence of Covid-19; partly it’s because of the many development challenges the team didn’t anticipate. “I could write a book for you,” Gardiner says. “This game has been quite a learning curve. Obviously, we’re single-player RPG folks.” But it’s also down to a new commitment to run Fallout 76 through community test servers. For Wastelanders, that process started in January. Gun theft aside, it’s allowed Bethesda to enjoy a much less painful launch than the disaster of November 2018. “I feel a little robbed [by lockdown],” Baudoin says. “I would love to go through the office and give a huge round of high fives.” “We took our lumps on 76, and that is part of the process,” Gardiner adds. “But we left it all on the field here. All year we’ve worked on this and it’s finally paid off.” Fallout 76 players will be familiar with a message that often pops up in the corner of the screen: ‘The verdant season in The Forest has ended.’ For Bethesda Game Studios, it may have belatedly begun.